|

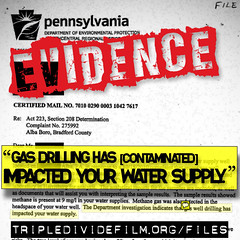

| Fracking Water Contamination (Photo credit: Public Herald) |

In the last year or two, leading US and Australian commentators have declared that, with the growth of shale fracking, the US, and even the world, has entered a new era of increased oil production.

It has been claimed, for instance, that we will see US 'energy independence', and more broadly a fundamental change in global oil supply.

But what are the facts?

The resource under question is now widely described as 'tight oil' because it is released by hydraulic fracturing of shale, or fracking. It is different from shale oil, which is produced by mining shale and heating it in retorts, at far higher cost.

A range of US interests are keen to exaggerate the significance of tight oil: the Obama administration wants a spirit of optimism to infuse the economy; US geopolitical commentators are keen to see America independent of foreign oil producers; the oil industry in general wants to emphasise that there's plenty of oil around for US consumers; large firms which have invested in fracking (like BHP Billiton) want to assure investors it's been a wise investment; and the drilling industry wants to talk Wall Street into continuing to finance their operations, a crucial ongoing requirement.

Also, fracking shale for oil has been conflated with fracking for gas, a more significant, though also exaggerated, development.

What are realistic, as opposed to boosters', figures on production, and likely trends?

The authoritative body on US oil production is the US Government Energy Information Administration (EIA), which puts out an Annual Energy Outlook (AEO). Current and estimated future production figures in the 2013 AEO simply do not support optimistic statements about US tight oil production.

Currently US liquid fuel consumption is about 19 million barrrels of oil a day (MBD), of which 40% is imported and 60% produced in the US. Tight oil contributes about 1.8 MBD, or about 10% of US consumption.

While this looks significant, it is only 2% of global production and according to the EIA, it will decrease from 2020 as the more productive tight oil 'sweet spots' are depleted.

Along with depletion of other US oil fields, overall import dependence will still be 37% after 2020. Basically, US tight oil will not offset either US or global depletion of oil supply.

A key aspect of tight oil is the rapid decline, often at 40% a year, in the volume of oil pumped per well, which is inherent due to the limited reach of fracking. This means that even highly profitable wells rapidly become unprofitable.

To maintain even a constant output, the level of drilling will have to constantly increase, meaning that a higher and higher oil price will be needed to support higher and higher costs of production.

Some tight oil extraction in the US may survive on a price of $80 a barrel, but more likely a price of $100 is needed. However, current tight oil production in the US is based on favourable, temporary conditions, which almost certainly it will not be replicated in other countries.

In other words, a long term oil price much higher than $100 a barrel would be necessary for tight oil to make any impact on global supplies.

Such an ever-increasing oil price would at some point choke off demand, so that a price ceiling will likely operate eventuallyto limit the extent of tight oil.

Unbiased observers of the US tight oil scene have therefore concluded that it is more a case of a brief boom followed by a dwindling away of a resource, than a large, long term contribution to oil supply.

What are the implications for Australia? One is that a tight oil bonanza is very unlikely here, because we don't have factors unique to the US.

These are: the rapid creation in recent years of excess drilling capacity for shale gas, which then became temporarily available at low cost for oil drilling; a highly developed and entrepreneurial drilling industry; finance available from Wall Street for high-risk US investment; extensive infrastructure in place to transport and refine oil; tolerant regulatory regimes; copious local water resources large enough to supply the heavy demands of fracking; and the ownership of underground minerals, under US law, residing with the landowner, thus removing dispute potential.

Another implication is that the US will not achieve 'energy independence'. It will still be a net oil importer (though even 100% self-sufficiency would not in fact mean independence from global market pressures). Given the importance of the US, this has geopolitical significance.

A third implication is that tight oil, at an oil price the world can afford to pay, is unlikely to greatly delay the shrinking of global oil supply. The lesson for Australia is that we need to plan for this shrinking supply, and the related rising price of oil.

Despite the essential role of oil throughout Australian society, there are no signs that our governments are planning for this in any way.