|

| Monica Richter |

[ED: Opinions on this article would be very much appreciated].

WWF-Australia has launched a program to engage corporate giants such as Westpac, Nestle Oceania and IKEA in contributing to a zero carbon economy by mid-century, powered by 100% renewable energy.

The Australian launch of the “Road to Paris and Science Based Targets” initiative tomorrow (Friday) in Sydney will begin the conversation on how the corporate world can engage with global climate change initiatives and develop practical pathways towards zero carbon.

WWF’s business engagement manager Monica Richter said the initiative was the result of an international collaboration between WWF, CDP, the UN Global Compact and the World Resources Institute.

Ms Richter said the initial launch would bring together firms across sectors including property, major retailers, banking and consumer goods for a “very broad conversation” with a focus on peer-to-peer learning and information exchange.

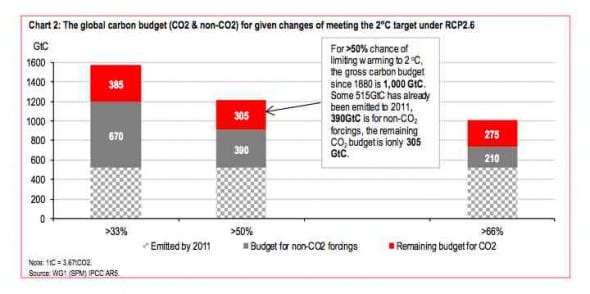

She told The Fifth Estate the challenge lay in setting targets that ensured the economy moved to a zero carbon economy by mid-century in order to keep climate change within the two degree warming limit. “Part of that is moving towards 100% renewable energy,” she said.

Finding the opportunities to increase renewable energy purchasing

This was the basis of the second initiative, a corporate renewable energy buyers group, which WWF was soon to launch in Australia. A similar initiative in the US by WWF, Rocky Mountain Institute and World Resources Institute has so far attracted at least 24 major corporations including IKEA, Unilever, Adobe, HP, 3M, Johnson and Johnson, Cisco, Bloomberg, Facebook and Volvo.

The US collaboration has identified key principles the corporations believe will support the greater uptake of renewable energy. These include:

- greater choice in procurement of renewable energy

- cost-competitiveness between traditional and renewable energy tariffs

- access to longer-term, fixed-price renewable energy

- increased access to third-party financing vehicles

- standardised and simplified processes, contracts and financing for renewable energy projects

- opportunities to work with utilities and regulators to expand choices for buying renewable energy

- See the full guide and principles

The network will also identify and discuss the barriers.

“There is agreement on the barriers,” Ms Richter said. “We will be looking at areas of collaboration and opportunity, whether it is a group of companies in the CBD jointly investing in a renewable energy project, or something like a bulk purchase arrangement via a power purchase agreement,” Ms Richter said.

“The aim is to facilitate a conversation to look at renewable energy beyond the [Renewable Energy Target]. The feedback I have been getting is companies want to collaborate.”

She said while uncertainty around the RET had impacted on jobs and investment, this initiative was one way of being proactive and constructive.

The organisation is also actively assisting with the development of the business case for individual projects. Brisbane Airport is one of them, and Ms Richter said renewable energy was on the cards for the airport as it wants to be “the greenest airport in Australia”.

The property supply chain can do its bit

Ms Richter recently spent 12 months away from her Sydney-based WWF office working on supply chain issues across hard and soft commodities. The organisation internationally is looking to such issues as a means of fulfilling its core mission of conservation of species and reducing human societies’ ecological impact on the planet.

“That’s where our market transformation work around supply chain and renewables fits,” Ms Richter said. "If we improve land management, we protect the places that we love. And climate change is equally a risk [to places such as the Great Barrier Reef].”

In Australia the property sector should be looking at its supply chain for materials such as cement, timber, glass and steel in terms of negative impacts and positive opportunities, she said. “[The property sector] is only just starting to come to terms with supply chain.”

That also included aspects such greenhouse gas emissions and low-VOC materials in the supply chain.

On steel

One material that is currently being focused on is the supply chain of structural steel. WWF is involved with a steel stewardship forum comprised of a number of stakeholders, including Bluescope, on the development of a standard for responsible steel.

One of the recent innovations that could contribute to such a product is a CSIRO project in Victoria that piloted the use of biochar to replace 50 per cent of the coking coal used in the steel-making process.

Ms Richter pointed out that solid wastes from the urban environment could be converted to biochar and biodiesel via pyrolisis. The biochar could be used for making lower-emissions steel and fed back into the built environment, and airlines such as Qantas and Virgin were looking at ways to use biodiesel in jet fuels to lower emissions from air travel.

While the federal government has cut funding for the CSIRO research, Ms Richter said it was a clear example of how new industries could be created and how the property sector could take a more integrated view of materials.

“Different industry sectors need to be doing their fair share,” she said.