|

| (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

Current greenhouse gas concentrations could warm the world 3-7℃ (and on average 5℃) over coming millennia. That’s the finding of a paper published in Nature today.

The research, by Carolyn Snyder, reconstructed temperatures over the past 2 million years. By investigating the link between carbon dioxide and temperature in the past, Snyder made new projections for the future.

The Paris climate agreement seeks to limit warming to a “safe” level of well below 2℃ and aim for 1.5℃ by 2100. The new research shows that even if we stop emissions now, we’ll likely surpass this threshold in the long term, with major consequences for the planet.

What is climate sensitivity?

How much the planet will warm depends on how temperature responds to greenhouse gas concentrations. This is known as “climate sensitivity”, which is defined as the warming that would eventually result (over centuries to thousands of years) from a doubling of CO₂ concentrations in the atmosphere.

The measure of climate sensitivity used by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) estimates that a doubling of CO₂ will lead to 1.5-4.5℃ warming. A doubling of CO₂ levels from before the Industrial Revolution (280 parts per million) to 560ppm would likely surpass the stability threshold for the Antarctic ice sheet.

As the world warms, it triggers changes in other systems, which in turn cause the world to warm further. These are known as “amplifying feedbacks”. Some are fast, such as changes in water vapour, clouds, aerosols and sea ice.

Others are slower. Melting of the large ice sheets, changes in the distribution of forests, plants and ecosystems, and methane release from soils, tundra or ocean sediments may begin to come into play on time scales of centuries or less.

Other research has shown that during the mid-Pliocene epoch (about 4.5 million years ago) atmospheric CO₂ levels of about 365-415ppm were associated with temperatures about 3-4 °C warmer than before the Industrial Revolution. This suggests that the climate is more sensitive than we thought.

This is concerning because since the 18th century CO₂ levels have risen from around 280ppm to 402ppm in April this year. The levels are currently rising at around 3ppm each year, a rate unprecedented in 55 million years. This could lead to extreme warming over the coming millennia.

More sensitive than we thought

The new paper recalculates this sensitivity again - and unfortunately the results aren’t in our favour. The study suggests that stabilisation of today’s CO₂ levels would still result in 3-7℃ warming, whereas doubling of CO₂ will lead to 7-13℃ warming over millennia.The research uses proxy measurements for temperature (such as oxygen isotopes and magnesium-calcium ratios from plankton) and for CO₂ levels, calculated for every 1,000 years back to 2 million years ago.

Some other major findings include:

The Earth cooled gradually to about 1.2 million years ago, followed by an increase in the size of ice sheets around 0.9 million years ago, and then followed by around 100,000-year-long glacial cycles.

Over the last 800,000 years, and particularly during glacial cycles, atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations and global temperature were closely linked.

The study shows that for every 1℃ of global average warming, Antarctica warms by 1.6℃.

So what does all this mean for the future?

Global warming past and future, triggered initially by either changes in solar radiation or by greenhouse gas emissions, is driven mainly by amplifying feedbacks such as warming oceans, melting ice, drying vegetation in parts of the continents, fires and methane release.

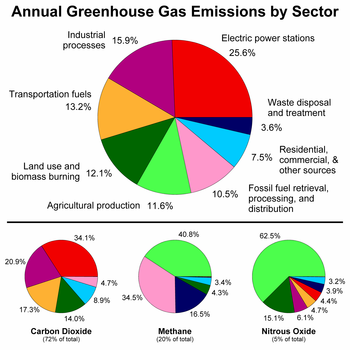

Current CO₂ levels of around 400ppm, combined with methane (rising toward 1,900 parts per billion) and nitric oxide (around 310ppb), are already driving such feedbacks.

According to the new paper, such greenhouse gas levels are committing the Earth to extreme rises of temperature over thousands of years, with consequences consistent with the large mass extinctions.

The IPCC suggests warming will increase steadily as greenhouse gases increase. But the past shows there will likely be abrupt shifts, local reversals and tipping points.

Abrupt freezing events, known as “stadials”, follow peak temperatures in the historical record. These are thought to be related to the Mid-Atlantic Ocean Current. We’re already seeing marked cooling of ocean regions south of Greenland, which may herald collapse of the North Atlantic Current.

As yet we don’t know the details of how different parts of the Earth will respond to increasing greenhouse gases through both long-term warming and short-term regional or local reversals (stadials).

Unless humanity develops methods for drawing down atmospheric CO₂ on a scale required to cool the Earth to below 1.5°C above pre-industrial temperature, at the current rate of CO₂ increase of 3ppm per year we are entering dangerous uncharted climate territory.

Andrew Glikson, Earth and paleo-climate scientist, Australian National University.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.