At the same time, the movement to stop climate change is also making history - last year the United States saw the

biggest climate march in history, as well as the growth of a fossil fuel divestment movement (the

fastest growing divestment campaign ever), and a steady drumbeat of local victories against the fossil fuel industry.

In short, the climate movement, and humanity, is up against

an existential wall: Find ways to organize for decisive action, or face

the end of life as we know it. This is scary stuff, but if you think no

movement has ever faced apocalyptic challenges before, and won, then

it’s time you learned about the Nuclear Freeze campaign.

Following Ronald Reagan’s election in 1980, the global anti-nuclear

movement also stood up to a global existential crisis - one that was also

driven by a wealthy power elite, backed by faulty science and a feckless

liberal establishment that failed to mobilize against a massive threat.

The movement responded with new ideas and unprecedented numbers to help

lead the world towards de-escalation and an end to the Cold War.

Under the banner of the Nuclear Freeze, millions of people helped

pull the planet from the brink of nuclear war, setting off the most

decisive political changes of the past half century.

The freeze provides

key lessons for the climate movement today; and as we face up to our

own existential challenges, it’s worth reflecting on both the successes

and failures of the freeze campaign, as one possible path towards the

kind of political action we need.

-

A short history of the Nuclear Freeze campaign

In 1979, at the third annual meeting of Mobilization for Survival, a

scientist and activist named Randall Forsberg introduced an idea that

would transform the anti-nuclear weapons movement. She called for a

bilateral freeze in new nuclear weapons construction, backed by both the

United States and the Soviet Union, as a first step towards complete

disarmament.

Shortly afterwards, she drafted a four-page “

Call to Halt the Nuclear Arms Race”

and worked with fellow activists to draft a four-year plan of action

that would move from broad-based education and organizing into decisive

action in Washington, D.C.

Starting in 1980, the idea took hold at the grassroots, with a series

of city and state referendum campaigns calling for a Nuclear Freeze,

escalating into a massive, nationwide wave of ballot initiatives in

November 1982 - the largest ever push in U.S. history, with over a third

of the country participating.

The movement also advanced along other roads: In June 1982, they held

the largest rally in U.S. history up to that point, with somewhere

between 750,000 and 1 million people gathering in New York City’s

Central Park, along with countless other endorsements from labor, faith

and progressive groups of all stripes. Direct action campaigns against

test sites and nuclear labs also brought the message into the heart of

the military industrial complex.

The effort continued into electoral and other political waters until

around early 1985, pushing peace measures at the ballot box and in the

nation’s capital, but never quite returned to the peak of mobilization

seen in 1982.

The impact of this organizing was palpable: President Reagan went

from calling arms treaties with the Soviets “fatally flawed” in 1980,

and declaring the USSR an “evil empire” in a speech dedicated to

attacking the freeze initiative in 1983, to saying that the Americans

and Soviets have “common interests … to avoid war and reduce the level of

arms.”

He even went so far as to say that his dream was “to see the day

when nuclear weapons will be banished from the face of the earth.” The

movement’s popular success led the president to make new arms control

pledges as part of his strategy for victory in the 1984 election.

-

“If things get hotter and hotter and arms control remains an issue,”

Reagan explained in 1983, “maybe I should go see [Soviet Premier Yuri] Andropov and propose eliminating all nuclear weapons.”

Reagan’s rhetorical and policy softening in 1984 opened the door for

Mikhail Gorbachev - a true believer in the severity of the nuclear threat,

and an advocate for de-escalation - to rise to power in the Soviet Union

in 1985.

Gorbachev’s steps to withdraw missiles and end nuclear testing,

supported by global peace and justice movements, created a benevolent

cycle with the United States that eventually brought down the Iron

Curtain and ended the Cold war.

Although the freeze policy was never formally adopted by the United

States or Soviet Union, and the movement didn’t move forward into full

abolition of nuclear weapons, the political changes partially initiated

by the campaign did functionally realize their short term demand. As a

result, global nuclear

stockpiles have indeed been declining since 1986, as the two superpowers began to step back from the nuclear brink.

The climate movement has room to grow

While the Nuclear Freeze shows that movements can move mountains - or

at least global super powers - it also shows that the climate movement

isn’t yet close to doing so. For starters, its size is not at the scale

of where it needs to be - not by historical measures, at least.

The

largest mobilization of the Nuclear Freeze campaign was the largest

march in U.S. history up to that point, and included double the number

of people who participated in the People’s Climate March.

The referendum

campaigns that reached their peak later in 1982 were historic on a

different scale as well: They were on the ballot in 10 states,

Washington, D.C., and 37 cities and counties, before going on to win in

nine states and all but three cities. The vote covered roughly a third

of the U.S. electorate.

This was a movement powered by thousands of local organizations

working in loose, but functional, coordination. Even in 1984, which is

generally considered after the peak of the Nuclear Freeze campaign, the

Freeze Voter PAC

(created at the Nuclear Weapons Freeze Campaign conference in St. Louis

in 1983) included 20,000 volunteers in 32 states - an electoral push thus

far unmatched in the climate movement’s history.

At the same time, this moment also showed how quickly movements can

decline. While the Nuclear Freeze campaign thrived in the very early

1980s, press and popular attention rapidly dissipated.

There are many

possible reasons that could explain this: from a shift in strategy away

from grassroots campaigns towards legislative action (the Nuclear

Weapons Freeze Campaign conference moved from St. Louis to Washington,

D.C., around this time), to a softening of President Reagan’s nuclear

posture, taking the wind out of the movement’s sails.

The real answer is

probably a combination of all of the above. From a peak of organizing

in 1982-83, participation in the movement significantly declined by the

mid-1980s, and mostly dropped off the political radar well before 1990.

Photo from Shutterstock.

Fear is a real motivator and a real risk

What drove the initial outpouring of action? In no small part, it was

fear. As Morrisey, lead singer of The Smiths, sang in 1986, “It’s the

bomb that will bring us together.”

In the late 1970s, research about the survivability of a nuclear

conflict became dramatically clearer, showing that even limited nuclear

exchanges could threaten all life on Earth. Also in this period,

Physicians for Social Responsibility initiated a widespread education

campaign that dramatized the local impacts of nuclear conflict on cities

around the country.

These developments, combined with the real impact

of Reagan’s escalatory rhetoric, created fertile ground for the freeze

campaign, allowing movement voices to appear more reasonable than the

technocratic nuclear priesthood that had lost touch with the public’s

fears. Only when Reagan began to step back his posturing and present

alternative arms control proposals was he able to blunt the power of the

movement.

The debate about the use of fear in the climate movement is ongoing,

but compared to the debate about nuclear weapons, the mainstream climate

movement under-appeals to the fear of climate change.

While it’s clear

that apocalyptic, decontextualized appeals to fear are demotivating,

grounded assessments of the problem that speak honestly about how scary

the problem really is, and are attached to feasible solutions are

crucial to mobilizing large numbers of people.

One example of an

effective appeal to fear was Bill McKibben’s widely-read 2012

Rolling Stone article “

Global Warming’s Terrifying New Math,”

which succeeded for several reasons: First, it used specific,

scientifically grounded numbers to explain approaching thresholds for

serious change. Secondly, it also was connected to a new, national

organizing effort to divest from fossil fuels, including a 21-city tour

that provided critical mass to begin campaigning.

Nevertheless, fear is, by its nature, hard to control and - in the case

of the freeze campaign - it provided an opportunity for co-optation of

the movement’s rhetoric. Most significantly, President Reagan’s Star

Wars program was able to redirect the fear of nuclear exchange into a

technocratic, bloated military project - rather than solutions to the root

cause of the problem.

The Reagan administration drew on the president’s

personal charisma and reflexive trust in the power of the military

industrial complex to transform some of the concern generated by the

movement, and turn it towards his own ends.

The climate movement faces a similar threat from technical solutions

that benefit elites, such as crackpot schemes to geo-engineer climate

solutions by further altering the Earth’s weather in the hopes of

reversing planetary heating, as well as other unjust ways of managing

the climate crisis. Discussions about big problems need to be paired

with approachable, but big solutions.

-

One simple demand

The Nuclear Freeze proposal turned the complex and treacherous issue

of arms control into a simple concept: Stop building more weapons until

we figure a way out of the mess. It was a proposal designed to be

approachable in its simplicity, and careful in the way it addressed

competing popular fears of both nuclear annihilation and perceived

Soviet aggression.

The idea of a bilateral freeze - the United States stops building if

the Soviet Union does too - handled both of these concerns in a way that

made the nuclear problem about growing arms stockpiles, not the

specifics of Cold War politics.

Even though the movement against nuclear

weapons had existed as long as the weapons themselves, the idea of the

bilateral freeze turned arms control much more into the mainstream of

American political discussion at a moment of real escalation with the

Soviets.

In a certain way, climate change is simple too: We need to stop

building fossil fuel infrastructure wherever there are viable renewable

or low-carbon alternatives, and do it quickly. Growing the movement in

this moment will require bold, bright lines that provide moral

directness and opportunities to take giant leaps forward in terms of

actual progress to reduce carbon emissions.

The simplicity of the freeze idea was intentional. At their meeting

in 1981, the Nuclear Weapons Freeze Campaign made it clear that the path

to power was not through access in Washington, but through “recruiting

active organizational and public support” - a strategy that required

demands that were easy and quick to explain.

Developing such active public support was a wide-ranging process, but

the campaign distinguished itself from other contemporary peace

movements by its use of the electoral system - first via local and state

referendums in 1980-82, and then with initiatives like Freeze Voter in

1984.

The referendum strategy, in particular, was a tool that offered

intuitive, broad-based entry points for organizing with clear steps for

participants. And it worked: The freeze campaign won an overwhelming

number of the referendums it was a part of in 1982.

Combined with

demonstrations, education campaigns and other grassroots actions, this

strategy allowed the movement to translate public sympathy into

demonstrable public support.

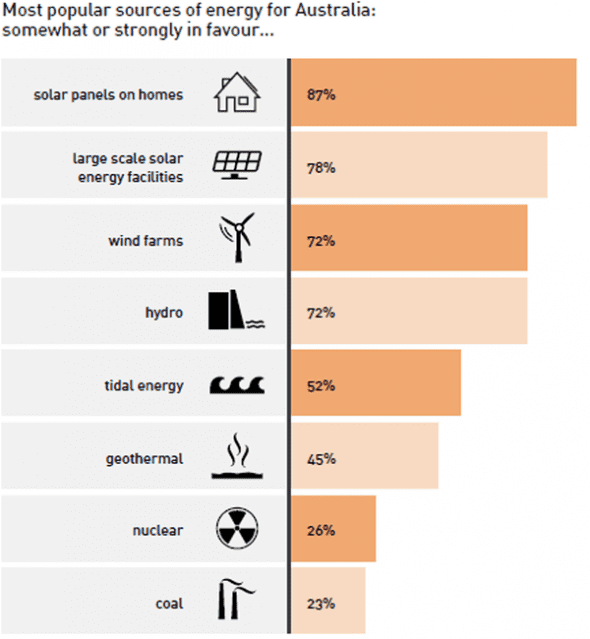

It is possible that the current moment in the climate debate could be ripe in a similar way. The public

broadly favors more climate action

, but is faced with relatively few meaningful opportunities to act on

it. The task of growing the climate movement is in many ways a task of

activating these people with opportunities for deeper involvement.

Other lessons learned

An important caveat must be made when discussing the breadth of the

freeze campaign’s support. Its demographics - mostly white and more middle

class than the public at large - reflected those of the establishment

peace movement from which it came.

That lack of diversity not only

represents a failure of organizing, but also could have contributed to

the movement’s lack of staying power and lasting political potency.

While at least one key freeze organizer I spoke with said explicitly

that the climate movement is succeeding in this regard in ways they

never did, the experience of the Nuclear Freeze explains just a few of

the perils of failing to create a real diverse climate movement. This is

a challenge that will take work throughout the life of the climate

movement, but it’s at least underway in some key regards.

The freeze campaign thrived on an initial wave of activism that was

grounded in local organizing via the referendum strategy. But after

organizing shifted (perhaps prematurely) more towards legislative

strategies, the next steps for the hundreds of thousands of people

involved in the campaign never emerged.

After the freeze became

mainstream discourse - supported by hundreds of members of Congress,

presidential candidates and millions of voters - the next step towards

disarmament remained murky.

Ultimately, the referendum strategy was symbolic: Cities and states

did not have any formal power over U.S. or Soviet nuclear arsenals. But

symbols matter, and so does democracy.

The overwhelming vote for the

freeze in 1982 shifted the political ground out from underneath liberal

hawks and the president, allowing more progressive voices to ride the

movement’s coattails - to the point where the 1984 Democratic Party

platform included a freeze plank. In other words, it turned diffuse

public opinion into a concrete count of bodies at the polls.

The referendum vote also asserted the right of people to decide such

weighty issues, taking them out of the realm of the military industrial

complex and into the light of day. When asked, people wanted a chance to

be involved.

The massive and democratic nature of the freeze campaign

struck a blow against the social license of the nuclear industrial

complex by yanking the implied consent of the majority of the American

people from both the military’s leadership and their tactics.

The path forward in an uncertain time

As the divestment movement grows, particularly on college

campuses - another effort aimed at the social license of an entrenched and

distant power elite - the lessons of the freeze campaign suggest that the

climate movement will need to answer many important questions in the

coming months and years.

We know how to march, but what comes next? Public opinion has

shifted, perhaps decisively, but how do we turn that diffuse energy into

a story about the need for action? If we mobilize in 2016 for the

election, what comes in 2017? And if we organize towards a single big

demand, as the Freeze campaign did in the 80s, how will we translate

that into ongoing power?

The climate movement faces an epic, unique struggle, but the

challenges it faces as a movement are not as singular as some may think.

As the movement ventures onto new ground, it’s worth remembering that

others have done what felt like the impossible, in the face of an

uncertain future - and triumphed.

The author thanks Freeze campaign activists Leslie Cagan, Randy

Kheeler, Joe Lamb, and Ben Senturia for supporting the research of this

article.

Duncan Meisel wrote this article for Wagingnonviolence.org. Duncan is a Brooklyn-based climate activist, writer and movement history nerd. He'll debate you over Twitter at @duncanwrites.