|

| (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

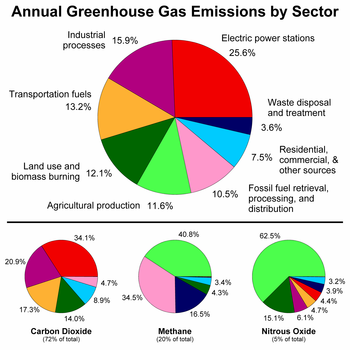

It’s now almost certain that 2015 will be the warmest year ever recorded. However, rather than reduce greenhouse gas emissions - something that has to happen quite urgently in order to avoid crashing through the safety barrier of 2℃ warming - we continue to pump more into the atmosphere.

Thus far, the collective international response to climate change has been similar to a frog passively sitting in heated pan of water. We are in danger of being cooked alive from inaction.

We will have to wait and see if the latest and largest UN climate change summit in Paris will buck this trend and produce effective responses to climate change. Previous meetings have exposed a bewildering spectrum of issues, concerns, vested interests and general political dysfunction. By comparison, the physical science of climate change is simple.

Why has it proved so difficult to agree to limit carbon emissions?

One reason stems from the fact the Earth’s atmosphere is a public good, just like street lighting, schools or public parks. A public good is non-rivalrous in that my use of it does not reduce your or anyone else’s access to it. A stable climate is a global public good as it is something all of humanity enjoys. We all, to a greater or lesser extent, affect it too. It makes no difference if carbon dioxide is released in Beijing, Birmingham or Baltimore.

If the atmosphere is a global public good then, in the absence of enforcement via international law to limit carbon emissions, you may conclude we are doomed. There is nothing to stop someone from emitting more than their fair share - this is the free rider problem.

If enough people act selfishly (and much of economic theory begins with the assumption that humans are self-interested), then the Earth’s sinks for carbon pollution will be swamped and dangerous climate change will ensue. This would be an example of a tragedy of the commons which has become an influential feature of western economic thinking since the latter half of the 20th century. However, the situation is perhaps not quite so clear cut.

Can we avoid climate tragedy?

In 2009, US political scientist Elinor Ostrom received the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences for her work on the management of public goods and common-pool resources. What Ostrom established is that, contrary to certain grim predictions, there are numerous examples of effectively managed public goods: Nepalese forests, American lobster fisheries, community irrigation schemes in Spain and many other systems are looked after sustainably through following a combination of eight principles.

The implications are profound. Rather than assume the market or central control are the most effective mechanisms to manage goods and services, Ostrom showed that groups of people can self-organise around common interests.

But it hasn’t escaped the attention of those trying to get international agreement on greenhouse gas emissions that some of these principles will not apply. In fact, if you are feeling particularly pessimistic, these principles can almost serve as a checklist of why such agreement will prove impossible. National boundaries do not stop the circulation of atmospheric gases, for instance, and there is no international body to police and enforce carbon emissions.

Global concerns, local action

So it seems all the more remarkable that agreements to limit carbon emissions and even reduce them from the atmosphere have been achieved. What’s more, these agreements are popping up all over the place.

More than 80 major cities across the globe are currently coordinating climate action. There are now a number of carbon trading communities that encompass a range of states in North America. EU member nations have agreed binding reductions while earlier this year the two largest emitters of carbon dioxide, the US and China, established important bilateral commitments to control carbon emissions in their respective countries.

These are all examples of polycentric governance. Having multiple levels of organisation allows flexibility and effective regional solutions to some of the obstacles that large, rigid governance can produce.

Are such efforts sufficient to avoid dangerous climate change? No. Nor are the national commitments to reduce emissions ahead of Paris. But what these regional initiatives show is that local communities can act independently of international agreements by making a global public good a local concern.

This may still seem puzzling to some economists and political scientists. While some of these initiatives make economic sense, what is the good of unilaterally self-imposed emissions limits if other regions don’t play ball? The answer to this question not only points the way to more effective action, but highlights a gaping hole in some people’s and institutions' understanding of climate change: it’s the right thing to do.

Climate change is as much a moral issue as a scientific one. Taking more than your fair share is wrong. Changing the climate which leads to people being harmed is wrong.

Any effective agreement that emerges from Paris will not have come out of a vacuum, but as a consequence of many individuals' and communities' agitation for change - some locally, some through the internet.

If we are going to address climate change, then recognising our shared values and interests is crucial. Humans are fundamentally a social species. We’ve only very recently appreciated that we are also a planet-altering species. Our moral senses know intuitively what we need to do in the light of such knowledge. Our economic and political institutions need to catch up rapidly.

James Dyke, Lecturer in Complex Systems Simulation, University of Southampton

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.