|

| 250 year-old black oak in Hutcheson Forest (Myla Aronson) |

As I walk through the William L. Hutcheson Memorial Forest in Somerset, New Jersey, on this unseasonably warm March morning, I admire the 250 year-old oaks, towering above, reaching to the sky.

Although small (26 hectares), this forest is one of the only remaining old growth forests in New Jersey and appears on the US National Park Service’s registry of National Natural Landmarks.

Preservation of remnant woodlands without active monitoring and management plans is not enough to preserve biodiversity.

These oaks saw the founding of the United States of America; they were seedlings when the Stamp Act was approved by the British Parliament in 1765, sowing the political seeds of the American Revolution; saplings when the Declaration of Independence was signed in 1776; and began to produce acorns around the time the Bill of Rights was ratified in 1791. They’ve taught thousands of Rutgers University students over the last 70 years.

But as a forest ecologist standing amidst the oaks, I also see an unhealthy forest fragment that’s neither resilient to change nor capable of supporting the biodiversity it did 100 years, or even 50 years, ago. I notice there are no seedlings, no saplings, nothing to take the place of these oaks when they die, and they are dying rapidly; either from old age or windstorms, we are losing these oaks.

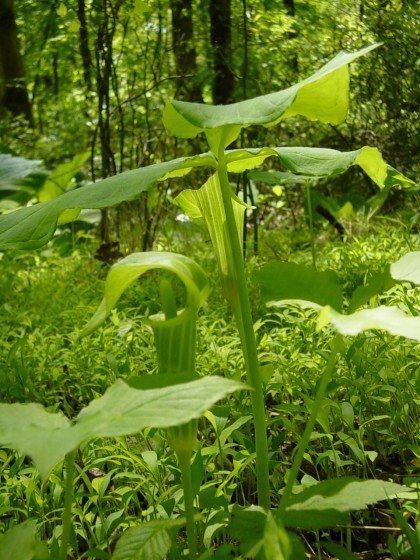

What will take their place? Thickets of invasive Multiflora Rose and Wineberry already dominate the light gaps created by the loss of many of the old oaks. In May, one used to be able to see hectares of Mayapple covering the forest floor, all of which are almost entirely gone now; in their place is a depauperate shrub and herb layer, missing native species.

Where are the next generation of oaks, and why have we lost them? What happened to the biodiversity of this forest?

In cities within the northeastern United States, small forest fragment remnants offer unique opportunities for human and non-humans alike. For us, forest fragments offer opportunities to interact with nature, to get away from the city, to learn, to exercise, to be at peace. For plants and animals, forest fragments are important for preserving biodiversity and are integral to the resilience of nature in the face of increasing urbanization and climate change.

Even small forest fragments support important species, such as the Kano palace bats in the city of Kano, Nigeria, recently discussed by Aliyu Barau. In and around urban areas, forest fragments are important habitats for migratory birds, functioning as stopover sites for both long- and short-distance migrants - as recently discussed by Mark Hostetler - and adding to continuity and connectivity of the landscape to support bird populations.

However, often there are assumptions that the preservation of forest remnants alone is sufficient to sustain their biodiversity. This stems from traditional forest successional theory, which holds that closed-canopy forests represent the stable end-point, with changes in species composition that are relatively minor over time.

But in reality, urban forests experience many stressors that decrease the resilience of these forests to both natural and urban disturbances, leading to large changes in plant species composition and, in turn, to degraded forest ecosystems. As land managers of urban forests know all too well, these changes are greater in magnitude and occur faster in human-dominated landscapes.

The capacity of these urban forest fragments to support biodiversity is threatened by the constant and interacting stressors of human use, air and soil pollution, exotic species invasions, and overabundance of white-tailed deer. Without constant management of these stressors, we face the loss of our forests and, with it, the loss of a rich American legacy: our biodiversity heritage.

For the past 13 years, I have studied the ecology of the Hutcheson Memorial Forest. Old growth forest fragments, such as this one, often offer a glimpse into our “biodiversity past” and should function as refugia for biodiversity in the face of human disturbance.

Old growth forests are endangered ecosystems, with less than 1 percent of forests in the eastern United States considered to be old growth. They are often viewed as reserves for genetic material and rare species, and are used as reference sites or “ecological benchmarks” for restoration of forest systems.

Many old growth stands have protected status, such as the Hutcheson Memorial Forest, but the majority of these forests are small parcels surrounded by suburban or urban development, posing special challenges to the management and preservation of these forests.

If these forests are to serve as benchmarks and refugia for species diversity, long-term monitoring is needed to understand how and if these forests function to maintain this diversity. Located in the New York metropolitan region, the most densely populated region in the United States, the Hutcheson Memorial Forest represents a model system within an iconic location to study the problems associated with conserving a significant resource in a suburban setting.

I have found that, since 1950, the Hutcheson Memorial Forest has changed drastically in both structure and composition. One of the markers of a healthy forest is the vertical diversity of vegetation structure. As you walk through a healthy forest, you should see many vegetation layers, from top to bottom: the canopy, with tall, mature trees that shade the forest; followed by the sub-canopy, comprising the trees growing to reach the canopy, which will be the next generation of canopy trees; then the shrub layer; and, finally, the herb layer on the forest floor. The animal diversity of the forest depends on these many layers of the forest.

The forest floor was rich in native wildflowers. Today, there is very little sub-canopy, Flowering Dogwood is almost completely extirpated from the forest, shrub cover has been reduced to 11 percent cover, and the wildflowers are patchy at best. Regeneration of the canopy oak and hickory trees is almost non-existent.

Invasive plant species have increased from rare in the forest to dominant components of each layer. Tree-of-Heaven (Ailanthus altissima), Multiflora Rose (Rosa multiflora), Garlic Mustard (Alliaria petiolata), and Japanese Stiltgrass (Microstegium vimineum) are now the dominant plant species in the forest, and all of these are invasive, non-native plants that outcompete native plants for space and resources.

The bird community at the Hutcheson Memorial Forest has shifted from being dominated by forest birds (Ovenbird, American Redstart) to dominated by birds typical of open woodlands and edges. This change in the bird community follows the change in vegetation closely.

The forest canopy is much more open now than in the past, with impenetrable thickets of invasive Wineberry (Rubus phoenicolasius) and Multiflora Rose, more typical of open woodlands than a closed-canopy old growth forest. Now, Wood Thrush, Gray Catbirds, Eastern Towhees, Rose Breasted Grosbeaks, White-Breasted Nuthatches, Hairy Woodpeckers, Blue Jays, and Northern Cardinals are typical of the forest. The forest also doesn’t appear to provide benefits to regionally declining forest bird species.

Garlic mustard and Japanese Stiltgrass, the most common invasive plants in the herb layer, outcompete native wildflowers and tree seedlings, causing regeneration failure. Gaps in the canopy, created by windstorms or the death of old trees - which, in a healthy forest, would allow sub-canopy tree species to fill in the gaps - creating a new generation of canopy trees, are instead filled with invasive species such as the Japanese Angelica Tree (Aralia elata; a newcomer to the forest in the last 10 years), Multiflora Rose, and Wineberry.

The change in the plants and birds at the Hutcheson Memorial Forest is an example of what happens to an urban forest when it is not actively monitored or managed over the long-term. This forest, while unique in its old growth character, fell victim to the same stressors all urban and suburban forests fragments share.

The enormous change in biodiversity character here shows us the importance of monitoring and active management to preserve biodiversity in our urban forest fragments.

At the Hutcheson Memorial Forest, no comprehensive vegetation surveys were performed between 1979 and 2003. If monitoring had occurred, it might have been possible to quickly identify and manage ecological and human threats. “Early detection, rapid response” is being adopted as a regional management for our threatened habitats and, if adopted at the Hutcheson Memorial Forest 25 years ago, would have countered these new stressors as they were introduced.

The “no-management” strategy, intended to be benign and to ensure biotic continuity, was based on deed restrictions originally written in 1955 to protect the forest from “builders, lumbermen, firesetters, hunters, and other destructive human influences”.

However, the urbanization of the surrounding area, the introduction of non-native species, and the overabundant white-tailed deer populations have changed the ecological playing field over the last 66 years. The no-management strategy has produced a heavily changed forest dominated by non-native, invasive species with little regeneration of the native tree, shrub, or wildflower species.

Without management of these non-native invasive plants and deer reduction efforts, the flora of the old-growth forest has progressively become composed of invasive, non-native plants and the few native species unpalatable to deer.

While the “no-management” strategy allows researchers to see the profound changes that a forest community undergoes in a suburban landscape, the role of this unique forest remnant, as well as other urban forest remnants, should be as references for regional diversity and refugia of native species diversity in this rapidly urbanizing world. These goals require proactive management of the multiple ecological stressors experienced by urban forest fragments.

The Hutcheson Memorial Forest was originally set aside, according to the property deed adopted when the land was donated to Rutgers University in 1955, for ecological study and for the “purpose of preserving the unspoiled virgin forest, flora, and fauna now existing therein in a state virtually untouched and unaffected by man and his civilization, making these premises a unique surviving example of such a natural environment”. The forest no longer represents this ideal.

However, over the last 10 years new monitoring and management goals have been established. Comprehensive bird and plant surveys have occurred over the last five years and will continue. A deer fence was erected in November 2015, and monitoring will occur frequently to assess how the forest plants and birds will respond to the reduction in deer herbivory.

Some invasive plants with small populations, such as Japanese Barberry (Berberis thunbergii), have been removed from the forest and have not been allowed to become invasive. Will the forest return to a biodiverse state, a refugia in a rapidly urbanizing landscape? Only time, monitoring, and active management will tell.

The Hutcheson Memorial Forest serves as a dramatic example of the need for monitoring and management in urban and suburban forests. Preservation of remnant woodlands without active monitoring and management plans is not enough to preserve biodiversity and is woefully inadequate for conservation goals.

Remnant forests in our cities are the primary greenspaces for preservation of native biodiversity. As the world becomes increasingly urbanized, these remnants will serve an even greater purpose: to conserve global biodiversity. City budgets are tight, but monitoring and management of urban forests should be a priority.

Preservation and clear targets for monitoring, research, and adaptive management activities in natural habitats should be a cornerstone of city master plans. Stressors on the ecological integrity of our diverse forests will continue to increase, but with monitoring and progressive management, we can save our unique biotic heritage.

Myla Aronson, New Brunswick

On The Nature of Cities

For More Information

William L. Hutcheson Memorial Forest: http://rci.rutgers.edu/~hmforest/

Aronson, M.F.J. and S. N. Handel. 2011. Deer and invasive plant species suppress forest herbaceous communities and canopy tree regeneration. Natural Areas Journal 31: 400-407.