|

| postcarbon.org |

Could declining world energy result in a turn toward authoritarianism by governments around the world? As we will see, there is no simple answer that applies to all countries. However, pursuing the question leads us on an illuminating journey through the labyrinth of relations between energy, economics, and politics.

The International Energy Agency and the Energy Information Administration (part of the U.S. Department of Energy) anticipate an increase in world energy supplies lasting at least until the end of this century. However, these agencies essentially just

match supply forecasts to anticipated demand, which they extrapolate from past economic growth and energy usage trends. Independent analysts have been questioning this approach for years, and

warn that a decline in world energy supplies—mostly resulting from depletion of fossil fuels—may be fairly imminent, possibly set to commence within the next decade.

Even before the onset of decline in gross world energy production we are probably already beginning to see a

fall in per capita energy, and also

net energy—energy that is actually useful to society, after subtracting the energy that is used in energy-producing activities (the building of solar panels, the drilling of oil wells, and so on). The ratio of energy returned on energy invested (EROEI) for fossil energy production has tended to fall as high-quality deposits of oil, coal, and natural gas are depleted, and as society relies more on unconventional oil and gas that require more energy for extraction, and on coal that is more deeply buried or that is of lower energy content. Further, renewable energy sources, especially if paired with needed energy storage technologies, tend to have a lower (some say much lower) EROEI than fossil fuels offered during the glory days of world economic growth after World War II. And

renewables require energy up front for their manufacture, producing a net energy benefit only later on.

The quantities and qualities of energy available to any society have impacts that ripple through its economy, and hence every aspect of daily life. As Lynn White,

Marvin Harris, and other anthropologists have shown, the political and social institutions of every society are determined—in broad strokes, though certainly not in the details—by what Harris called its

infrastructure, or its ways of obtaining energy, food, and materials. Abundant, easily transported and stored energy from fossil fuels made industrial expansion possible during the twentieth century, and especially after World War II. This period of turbo-charged economic growth had repercussions in fields as diverse as manufacturing, farming, transportation, and even music (via the electrification of live performance as well as the flourishing of the recording industry). That’s right: your favorite rock band is an epiphenomenon of fossil fuels.

Further, as archaeologist

Joseph Tainter has pointed out, societies often use complexity (an increase in the variety of tools and institutions) as a means of solving problems. But complexity carries energy costs, and the deployment of complexity as a problem-solving strategy is subject to diminishing returns. Tainter argues that this is a comprehensive explanation for the historic collapse of civilizations—one that has obvious implications for our own society: clearly, if its energy supplies are compromised, its capacity to successfully deploy complexity to solve problems will be impaired.

All of which suggests that if and when energy sources decline, industrial societies will face systemic challenges on a scale far beyond anything seen in recent decades. In this essay, I propose to examine just one area of impact—the realm of politics and governance. Specifically, I address the question of whether (and which) societies will have a high probability of turning toward authoritarian forms of government in response to energy challenges. However, as we will see, energy decline is far from being the only possible driver of authoritarian political change.

The Anthropology and History of Authoritarianism and Democracy

It is often asserted that democracy began in ancient Greece. While there is some truth to the statement, it is also misleading. Many pre-agricultural societies tended to be highly egalitarian, with most or all members contributing to significant decisions. Animal-herding societies were an exception: they tended to be patriarchal (men made most decisions), and, among men, elders and those with more property (women, children, and captives were treated as chattel) held sway. (Herders, whose social relations reflect the harshness of their environment, typically live in places unfit for farming, such as deserts.) A good example of democracy completely independent of the Greek tradition is the

Iroquois confederacy of the American northeast, whose inclusive decision-making system incorporated checks and balances; it served as an inspiration for colonists seeking to design a democratic government for themselves as they threw off the yoke of British rule.

Early agricultural societies were often rigidly authoritarian. Marvin Harris explained this development in infrastructural terms: stored grain surpluses required management and distribution authority, as did irrigation systems. But the appropriation of so much power by an individual or family required further justification; hence new sky-god religions emerged, valorizing kings and pharaohs as wielders of divine power. Greece, however, differed from Egypt and other “hydraulic” civilizations (i.e., ones based on huge irrigation systems): it enjoyed enough rainfall so that irrigation wasn’t required. Farmers could grow diverse crops independently, without relying on state controls over water and grain. Hence it was in Athens that democracy emerged (or re-emerged) as a political system—imperfect though it may have been (Attica’s total population was likely between 150,000 and 250,000, but free citizens numbered only 20,000 to 30,000: women, slaves, and foreigners could not participate in the public process of making decisions).

Prior to the fossil fuel era, Europe enjoyed a significant injection of wealth from its sail-based pillaging of much of the rest of the world. Merchants, as a social class, began to jostle against the aristocracy and clergy, previous holders of political power. Wealth and abundant energy supported the development of science and philosophy, which—when combined with newer technologies like the printing press—helped usher in the age of reason. The autocratic rationale for rule, “because God granted me divine power,” no longer seemed reasonable. In Britain, the monarchy began reluctantly to cede some of its authority to parliament during the mid-seventeenth century; then, a little over a century later, thirteen of Britain’s colonies in North America rebelled and formed a federated republic. Revolution in France further stoked demands throughout Europe and elsewhere—by philosophers and commoners alike—for wider distribution of political power.

In modern times, industrial expansion based on abundant energy from fossil fuels has led to urbanization and to the employment of much of the population in factory, sales, and managerial positions. This detachment of people from land has in turn produced greater geographic and social mobility, as well as opportunities to organize collective demands for power sharing (via trade unions and political organizations of all kinds), including women’s suffrage. Democracy has spread to more and more nations—always kept at least partly in check by centralized economic and military power. Meanwhile, an ever-greater mobility of capital, goods, information, and people has also led to the geographic expansion of polities—nations of larger size, alliances between nations, trade blocs, and an intergovernmental organization offering membership to all countries (the United Nations).

Now, in all likelihood, comes an era of declining and reversing economic growth, as well as reduced mobility. Existing forms of government will be challenged. Ultimately, larger political units may tend to break up into smaller ones, and many democracies may be vulnerable to authoritarian takeover. But the risks will vary significantly by country, based on geography and local history.

How Nations Succumb to Authoritarian Takeover

- Election of a dictator. Mussolini initially came to power in Italy through election, as did Hitler in Germany, Ferdinand Marcos in the Philippines, and “Papa Doc” Duvalier in Haiti. Why do people elect authoritarians? Typically, they do so because they feel threatened—by a foreign or domestic enemy, or by hard times—and want a strong man to take charge. Usually the elected authoritarian-in-waiting only assumes dictatorial power later, without asking the consent of the electorate. For example: in a recent essay, Ugo Bardi recounts how declining exports of British coal to Italy after World War I led to an energy famine, which in turn resulted in riots, shifting political alliances, and the rise of Mussolini and the Fascists.

“When Daniel Ortega was elected president in 2006 with a twiggy 38 percent victory, Nicaragua had a constitutional ban on consecutive reelection as a safeguard against dictatorship. . . . Eleven years later, Ortega is starting his third consecutive term as president after rewriting the constitution, banning opposition parties, and consolidating all branches of government under his personal control. Ortega orchestrated his power grab by polarizing the country, dividing the opposition, attacking congress, demonizing the press, forbidding protest, demanding personal loyalty from all government workers, and turning all his public appearances into campaign rallies for his core base of supporters. He institutionalized his cult of personality and normalized . . . threats of violence and chaos. . . .”

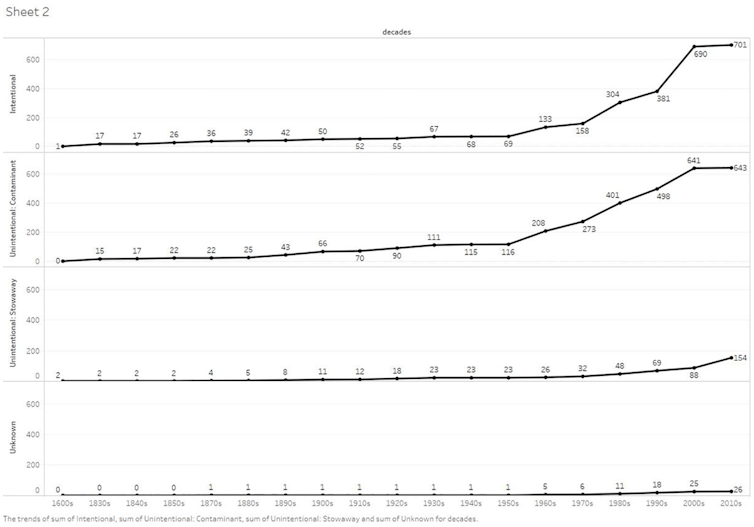

- Military coup. The list of military dictatorships in recent decades is long. Clayton Thyne and Jonathan Powell maintain a coup dataset, according to which there were 457 coup attempts worldwide from 1950 to 2010, most by military factions. Of these, about half were successful. The reason military putsches are so common is not hard to discern: the taking of power by armed force is likely to be most often—and most successfully—attempted by those who are already professionalized wielders of weaponry.

- Foreign interference or foreign support for a coup. If a powerful nation wishes to exert near-total control over a weaker country, one of the most effective ways to do so is to install a puppet dictator who can then be bribed and threatened. This is a strategy the United States has deployed often, beginning early in the twentieth century with its support for dictators in Central and South America. Also, in the early 1950s, the U.S. supported Shah Pahlevi over Iran’s elected President Mohammad Mossadegh, leading to decades of dictatorship there. However, the U.S. is far from the only country to have ruled other nations by remote control: Britain, France, and Russia/USSR did the same in one instance or another.

- Revolution. Most revolutions are fought against authoritarian regimes or foreign rulers. On rare occasions, however, the people—typically a rambunctious faction of the people—attempt to overthrow an elected government in favor of a would-be dictator. Such revolutions are usually more accurately described as civil wars. Coups in which an elected leader is overthrown in favor of an authoritarian with the help of foreign influence can be stage-managed to appear as revolutions (this happened in the case of Mossadegh in Iran). More frequently, however, revolutions that are widely intended to result in democratic reforms eventually result in the coalescing or emergence of an authoritarian regime (for example, in France at the end of the 18th century, in Russia in 1917, in China in 1949, in Cuba in 1959, and in Cambodia in 1963).

Risk Factors for Authoritarian Takeover

Economic decline led by energy decline probably won’t automatically result in despotism, just as industrialism and economic expansion didn’t everywhere lead to democracy. What are the circumstances that are likely to push nations to adopt more authoritarian governments?

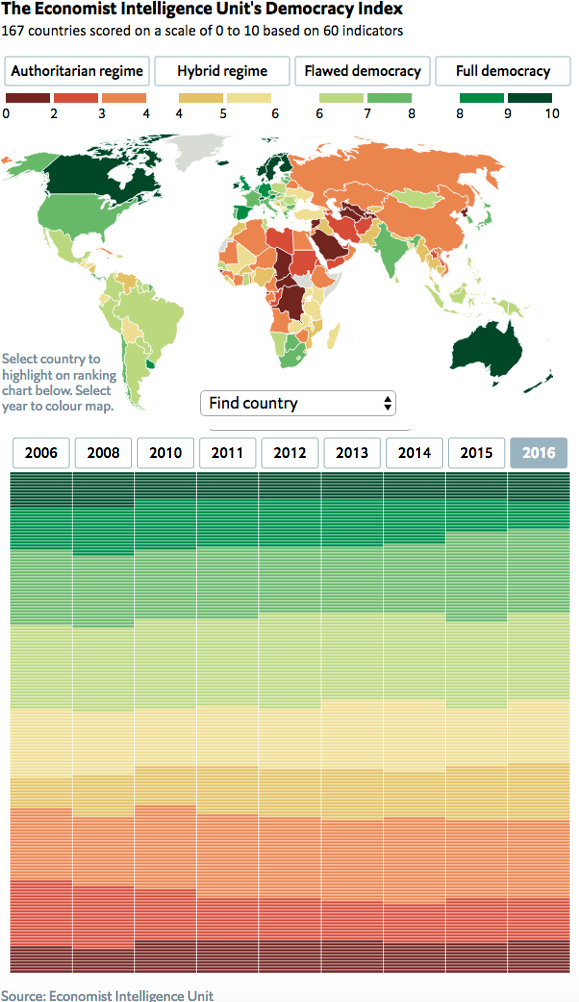

Below are some notable risk factors (this is not an exhaustive list). From here on, I will occasionally refer to the

Democracy Index (compiled by the UK-based

Economist Intelligence Unit), which seeks to measure the state of democracy in 167 countries based on 60 indicators.

- Economic decline or instability. Periods of high joblessness, disappearing savings, and declining incomes can lead to widespread dissatisfaction with government, offering an opening for demagogues, military coups, revolutions, or foreign takeovers.

- Weak democratic institutions with a short history. Democracy is a habit that needs reinforcement. It also needs institutions—parties and election machinery (polling places, fair counting of ballots, etc.). If those institutions have shallow roots, it is easier for them to be undermined or corrupted.

- Dysfunctional media. Democracy only functions if the public is well informed with regard to issues and the actions of government. Media organizations can become weak, dominated by special interests, polarized, or suppressed by government. Their ownership can be consolidated by a few companies with similar political interests. In our current age of electronic information, media are vulnerable to outright propaganda, “fake news” (i.e., reporting characterized by ideologically spun, inaccurate, or even wholly invented stories), and the clever use of social media (bots and trolls).

- High and growing levels of economic inequality. Some of the early observers of democracies, including Toqueville, noted that procedural democracy (equality before the law, universal voting rights, the right to express oneself in the political sphere) can be undermined by the power of wealth. Rich people can buy influence in ways both obvious and subtle. This is why healthy democracy is often correlated with progressive taxation and the availability of government-run social programs for those who are unemployed, retired, or sick.

- Simmering resentments among social/racial/religious/ethnic groups, offering fodder for scapegoating. In hard times, demagogues can play upon such resentments to gain support and take power.

- Deep political polarization. Polarization drains people’s attention from areas of shared interest and potential cooperation, and focuses it instead on points of disagreement. As each party demonizes the other, former political extremists may find their way into the mainstream. Polarization can offer an opening for a demagogue who promises to trounce the opposition party once and for all, if given dictatorial powers.

- Weak financial systems heavily dependent on debt. As economic historians have shown, heavy reliance on debt always results in an eventual financial crash. See “economic decline” above.

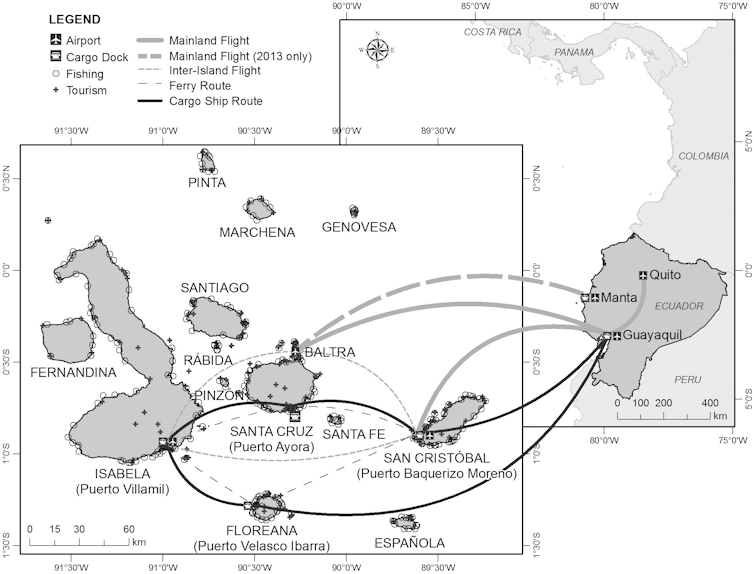

- Special vulnerability to foreign influence or takeover. If a country is militarily weak but has a strategically significant geographic location (for example, along the route of an important oil or gas pipeline), or if the country happens to possess strategically important resources (minerals or fossil fuels), more powerful nations are likely to have a keen interest in keeping that country controllable.

- A powerful military with a history of domestic intervention. If social chaos ensues for whatever reason, the military is likely to step in; and when it does it is more inclined to install a dictator than to restore or build a democratic system. That’s because the military itself, in virtually every nation, has an authoritarian internal structure. (The Iroquois insisted that peace chiefs be different from war chiefs—an idea borrowed by the framers of the U.S. Constitution, which specifies that no acting military leader may assume the presidency).

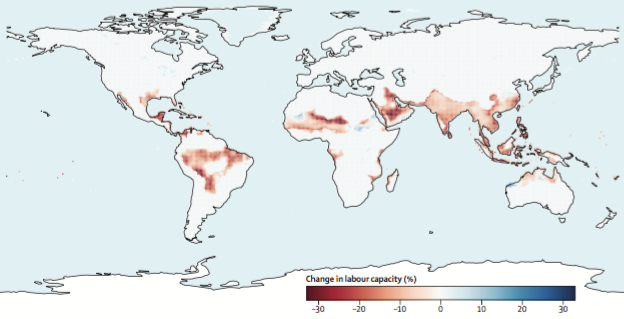

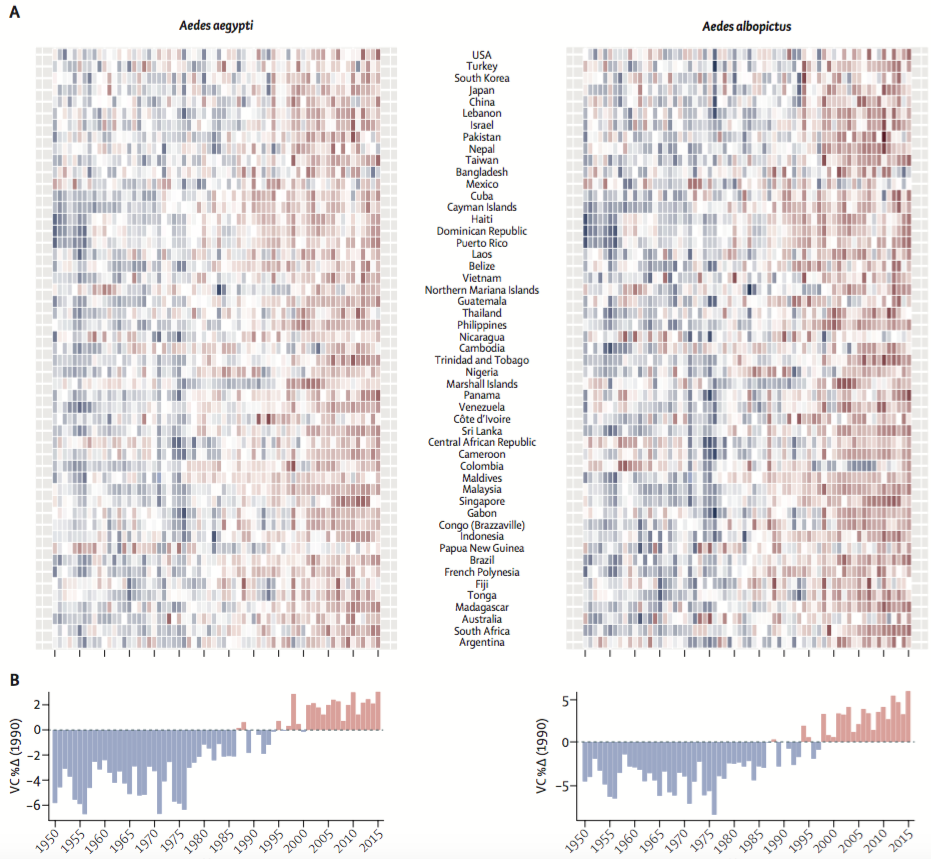

- Special vulnerability to climate change or other environmental disasters.People don’t inevitably turn to strong leaders after natural disaster. Over the short term, they tend instead to band together. Old grievances tend to be temporarily forgotten, and distinctions between rich and poor are at least somewhat erased. However, over the longer term, ecological disruption can lead to scapegoating and either revolution or a turn toward strong men who promise to restore order. For example, the Syrian civil war, which began in 2011, was preceded by a long and devastating regional drought linked to climate change; refugees from the countryside flooded cities, straining infrastructure already burdened by the influx of some 1.5 million refugees from the Iraq War. These refugees provided recruits for the Free Syrian Army, which rebelled against the authoritarian Assad regime.

- High population growth rate. Nations with high fertility rates typically find it difficult to overcome poverty, absent a robust resource-exporting economy. Indeed, of the ten nations that currently have the highest population growth rates (Lebanon, Zimbabwe, South Sudan, Jordan, Qatar, Malawi, Niger, Burundi, Uganda, and Libya), seven have fully authoritarian regimes according to the Democracy Index, while three have “hybrid” governments; only two (Qatar and Lebanon) have a per-capita GDP higher than the world average. As world energy declines, countries with fast-growing populations will probably see higher-than-typical per-capita decline rates in energy usage, likely leading to economic and social instability.

Most of the above might be considered generic risk factors, in that they apply to all societies even without taking energy decline into account. Other risk factors are more directly related to potential energy supply problems:

- A high dependency on food imports. History has shown (for example, in Egypt in 2011) that food shortages can rapidly lead to social unrest and ultimately to revolution or authoritarian takeover. High food import dependency is therefore a point of vulnerability in societies given the likelihood that energy decline will also entail a decline in mobility, including the movement of food and other necessary goods.

- Government’s budget tied to fossil fuel export revenues. If a government derives most of its revenues from fossil fuel exports, it will eventually face a declining revenue stream. Even Saudi Arabia, which has been a top oil exporter for decades, recognizes this (it is an authoritarian monarchy; several other major oil exporters are likewise classified as authoritarian regimes by the Democracy Index). Norway has sought to prepare for the inevitable by saving its oil export revenues in a permanent investment fund; currently that nation enjoys the highest rating of any country on the Democracy Index, and its citizens also rank high in terms of per capita income and self-reported happiness.

- High per capita energy usage. Countries that have high per capita rates of energy usage have further to fall as energy becomes harder to produce. Countries with low rates of per capita usage typically already have ways of meeting basic needs relatively simply and directly—with a higher percentage of the total population engaged in food production, and a more robust informal economy.

- High dependency on energy imports. If heavy dependence on revenue from fossil fuel exports can constitute a vulnerability for democracies, heavy dependence on imports can as well. Even though the U.S. was a major oil producer throughout the twentieth century, by 1970 it was increasingly dependent on imported crude; hence it faced economic hardship due to the 1970s Arab oil embargo.

There is something missing from these lists that is hard to define but nevertheless crucial to our present discussion. Perhaps Pankaj Mishra captures it best in his recent, difficult book,

The Age of Anger. There he describes how, from its beginnings in the eighteenth century, modern capitalist, urban, industrial life disrupted previous patterns of settled existence. People lost their connections with land and tribe, and traditional livelihoods, and hence some essential aspects of their identity. In return, economic liberalism promised mobility, comfort, and intellectual and moral advancement. Instead many experienced anonymity and alienation, and the result was widespread resentment. This in turn led to decades of revolution and terrorism in Europe throughout the nineteenth century, with many prominent assassinations (U.S. President McKinley, French President Marie François Sadi Carnot, Bavarian Prime Minister Kurt Eisner, Russian Czar Alexander II, Serbian King Aleksandar Obrenović, Spanish Prime Minister Juan Prim, and many others) as well as bombings and other violent events.

Today urbanization, commercialization, and technological disruption are proceeding at a faster pace than ever and reaching billions in formerly rural nations in East and South Asia, the Middle East, and Africa. Millions of young people are being educated for life as consumers and workers, yet are finding the promises of “development” ringing hollow. Unemployment rates among young males are often very high in these nations, and young men educated for urban industrial life are being attracted to militant fundamentalism. The rise of militant fundamentalism, along with high rates of immigration from fast-urbanizing countries, generates fear in the first-wave industrialized countries—a fear that leads to a rise in “traditionalism” and a turn toward authoritarian leaders who promise to suppress terrorism and reduce immigration. In effect, for both the young Islamist radical and the older Trump voter, tribalism is a powerful motivator. We will return to this subject later as we consider ways to counter or mitigate risks to democracy.

Typically, a surplus of unemployed young males also increases the likelihood of war. During wartime, the combatants gain a sharper sense of meaning and purpose. Democracy seldom flourishes during war, though it can persist and blossom anew afterward.

Current Case Studies

With so many risk factors at play, one would not expect to see a simple causal pathway connecting energy decline with a drift toward authoritarianism. Instead, while energy decline will constitute a new and unexpected stressor for industrial societies, it can be expected to exacerbate other existing risk factors in complicated ways. The nations most at risk for authoritarian takeover will be those that have the most such factors at play.

Indeed, as global net energy begins its inevitable slide we are indeed seeing an erosion of democratic institutions in many nations, along with warnings signs for increasing authoritarianism. The

2017 Democracy Index Report notes that “almost one-half of the world’s countries can be considered to be democracies of some sort, but the number of ‘full democracies’ has declined from 20 in 2015 to 19 in 2016. The U.S. has been downgraded from a ‘full democracy’ to a ‘flawed democracy.’” In 2016, “no region experienced an improvement in its average score and almost twice as many countries (72) recorded a decline in their total score as recorded an improvement (38). Eastern Europe experienced the most severe regression.”

Below are a few examples of nations, in order of population size, that are currently at various points on the democracy spectrum; each case study consists of a very brief discussion of some relevant risk factors.

- People’s Republic of China. With a one-party communist government, China is listed as an “authoritarian” country by the Democracy Index. Since economic liberalization began there in 1978, the country has seen rapid economic growth based mostly on energy from coal. China currently consumes over half the coal produced globally. However, domestic production is leveling off and is likely already in decline. China’s current president, Xi Jinping, assumed office in 2012 and has advanced far-ranging measures to enforce party discipline and internal unity. He initiated an anti-corruption campaign targeting prominent incumbent and retired officials, but has also imposed further restrictions over civil society and internet communications. For decades, China has controlled is population growth through legal restrictions on reproduction (the “one child policy”). As its economy has expanded and much of the population has moved to cities, income inequality has soared; resentment over this, especially in rural areas, has been largely held in check by the promise of further urbanization and growth. With the world’s largest population and second-largest economy, China is seeking greater geopolitical clout, but faces the prospect of widespread domestic unrest when growth finally and inevitably ends.

- India. This nation, which has long suffered from internal religious and ethnic friction, in 2014 elected Narendra Modi as prime minister. Modi has been described as a Hindu nationalist and has expressed sympathy for the Hindu extremist who assassinated the nation’s founder, Mohandas Gandhi, in 1948. India has long-simmering rivalries and border disputes with its neighbors, China and Pakistan. Its population is currently 1.3 billion, the second highest of all countries, with a growth rate of 1.26 percent, higher than the world average. The country has seen a high rate of economic expansion in recent years, based mostly on rapidly increasing rates of mining and burning coal. However, the limits of India’s coal are now within view. The Democracy Index currently lists the country as a “flawed democracy.”

- The United States. This is a country with deep democratic traditions that have become eroded and corrupted in recent decades (as noted above, the Democracy Index currently lists the U.S. as a “flawed democracy”). Rapid economic growth in the decades after World War II has moderated to a sluggish pace, with most economic benefits in recent years accruing to the top one percent of earners. Increasing economic inequality has stoked long-standing resentments among the working class. The current president, Donald Trump, played upon those resentments (against ethnic minorities, bicoastal elites, and immigrants) to achieve an upset election victory in 2016, promising to “make America great again.” Trump, a businessman and political novice, has advanced far-right policies and is widely regarded as having authoritarian tendencies. The nation’s high dependence on energy imports has declined in recent years due to a dramatic rise in its production of low-EROEI shale gas and tight oil (Trump is a strong supporter of fossil fuel producers). However, the country’s unconventional oil and gas production is set to commence terminal decline within the next few years. The Trump presidency is exacerbating already-deep political polarization within the U.S. and there is now public discussion about the possibility of mass violence, including armed insurrection if Trump is impeached. Trump’s competency is widely questioned, and for a number of reasons there are legitimate doubts that he will last his full four-year term in office.

- Following the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, Russia experienced sharp economic decline, population decline, and the pillaging of formerly publicly owned resources by wealthy “oligarchs”—former government officials-turned-entrepreneurs who often secretly expatriated large sums of cash. Many Russians blamed foreign interference, notably by the U.S., for their hard times. They elected Vladimir Putin, an obscure ex-KGB officer, as president in 2000 following a series of mysterious bombings, and he has remained in charge (either directly or via his political ally Dmitry Medvedev) up to the present. Putin purged some of the oligarchs and stabilized the nation’s economy, using revenues from fossil fuel exports, but wealth within the country is distributed highly unevenly: outside Moscow there is much poverty, and the favored remaining oligarchs (reputedly including Putin himself) have amassed vast fortunes. The Democracy Index lists Russia as an “authoritarian” country partly due to strict controls on press freedoms and problematic treatment of opposition political parties and candidates. Putin has advocated “traditionalism”—a far-right philosophy characterized by religious orthodoxy, nationalism, militarism, and a tendency to repress minority social groups (in this case including gays). While Putin’s grip on power seems secure for now, inevitable oil and gas export declines and extreme inequality could eventually lead to internal turmoil.

- The Philippines. This nation has a rapidly growing economy, averaging 6.1 percent per year from 2011 to 2015; its energy is derived mostly from imported fossil fuels. The Philippines’ population growth rate of 1.55 percent annually (with a doubling time of 47 years) is considerably higher than the global average. Its current president, Rodrigo Duterte, was elected in 2016. He is notable for his promise to crack down on illicit drug sales and use, and has employed death squads and the extrajudicial killings of reputed drug dealers to this end (Duterte admits to having carried out some extrajudicial killings personally). He has also promised to shift the nation’s alliances away from the U.S. and toward Russia and China. Duterte has the characteristics of a “strong man,” but has advocated for political decentralization. The country imports virtually all its energy supplies and its import rates are growing. Its population is expanding at over 1.5 percent annually, higher than the global average. The Democracy Index currently lists The Philippines as a “flawed democracy.”

- In 2011, Egypt was one of the primary nations seeing “Arab Spring” democratic uprisings, amid a catastrophic regional drought linked to climate change. These largely peaceful uprisings resulted in the downfall of long-time Egyptian dictator Hosni Mubarak and the election of Mohamed Morsi of the Muslim Brotherhood. The election was followed by clashes between supporters and opponents of Morsi. Egypt’s current leader, Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, came to power in the 2013 military coup that ousted Morsi. Officially president, el-Sisi has dictatorial power. After decades of dictatorship and outside influence from Britain (of which it was a protectorate from 1882 to 1952), Egypt’s brief democracy had shallow roots, if any. The Democracy Index currently lists Egypt as an “authoritarian” country. Its strategic location next to the Suez Canal contributed to a political, military, and economic event in 1956 known as the “Suez Crisis,” in which Egypt was invaded by forces of Israel, the UK, and France. Egypt is Africa’s fourth largest producer of oil and gas, but its production rates have declined in recent years and it is now a modest net importer of these fuels. The overwhelming majority of its food supplies are also imported. Its population growth rate is currently over two percent per annum, with a doubling time of less than 35 years.

- Saudi Arabia. One of the most repressive and authoritarian regimes in the world, this nation has an economy and government entirely dependent on oil exports. The government supports Wahhabism, an extreme Sunni Muslim sect, as its state religion; and it opposes Shiite Islam, which predominates in communities located close to country’s oilfields. An absolute monarchy, the Kingdom is currently officially ruled by the elderly King Salman, but his 31-year-old son Mohammad bin Salman bin Abdulaziz Al Saud, the Minister of Defense, is considered the power behind the throne. In recent years the Saudis have funded wars in Yemen and Syria, and have initiated economic and diplomatic hostilities against Qatar. Saudi Arabia’s wealth and the nation’s economy depend entirely on oil export revenues. Since the oil price collapse of 2014, the Saudi government has had to spend down its cash reserves. There are increasing signs of instability within the Kingdom: an armed insurrection in the predominantly Shiite town of Awamiya is currently being violently suppressed. A political crisis in this country would probably result in upheaval throughout the Middle East—an increasingly polarized and largely authoritarian region.

- For this nation the twentieth century was dominated by the long dictatorship of Juan Vicente Gómez (ruled from 1908 to 1935); economic expansion, corruption, and crises; and a series of coups punctuating periods of fragile democracy. The century ended with the Bolivarian Revolution of 1999, led by Cesar Chavez. This was a left-wing populist social movement and political process that sought to implement popular democracy, economic independence, equitable distribution of revenues, and an end to political corruption. Chavez sought to align his nation with socialist countries such as Cuba, and against the hemispheric hegemon, the United States. After Chavez’s death in 2013, his vice president, Nicolás Maduro, assumed the presidency and was elected to that office the same year. Since then Maduro has assumed increasingly dictatorial powers as the nation’s economy has virtually collapsed. Nearly all government revenues come from oil exports, and when the price of oil fell sharply in 2014 the nation’s economy worsened significantly (though Venezuela had already devalued its currency amid rising food shortages). Some of Venezuela’s troubles may trace to U.S. overt economic sanctions and covert operations. The country officially boasts the world’s largest oil reserves, but this is a highly misleading statistic as the great majority of its oil, categorized as “extra-heavy oil,” is slow and quite expensive to extract. The Democracy Index currently lists Venezuela as a “hybrid regime.”

- Formerly a satellite state of the Soviet Union, this nation is currently listed as a “flawed democracy” by the Democracy Index. Its current president, Viktor Orbán, assumed office in 2010 and is an advocate of what he calls an “illiberal state,” viewing the community, and not the individual, as the basic political unit. Politico has noted that his political philosophy “echoes the resentments of what were once the peasant and working classes” by promoting an “uncompromising defense of national sovereignty and a transparent distrust of Europe’s ruling establishments.” Orbán’s governing philosophy overlaps somewhat with Vladimir Putin’s “traditionalism.” Orbán is considered a “talisman of Europe’s mainstream right,” in that populist and right-leaning politicians throughout Europe, whose campaigns typically seek to exploit public concerns about immigration, terrorism, and economic stagnation, often look to Orbán as a model or ally. Hungary shares the rest of Europe’s increasing reliance on energy imports from Russia and the Near East.

- An independent republic since 1944, Iceland is listed as a “democracy” by the Democracy Index. Due to unique circumstances, all of the country’s electricity already comes from geothermal and hydropower, and the nation has a realistic goal to soon derive all energy from renewable sources (excepting the embodied energy in imported food and manufactured goods). Its population is only 332,530 (2016 estimate), with a population growth rate of 0.7 percent, below the global average. In 2003–2007, following the privatization of the banking sector, Iceland shifted its economy toward dependence on international investment banking and financial services. However, it was hard hit by the global financial crisis of 2008, and austerity policies instituted to stabilize the economy proved deeply unpopular. In 2016, Prime Minister Sigmundur David Gunnlaugsson resigned after being implicated in a tax evasion scandal, and early elections in 2016 brought in a right-wing coalition government.

Clearly, nations are in widely varying circumstances, with different areas and degrees of vulnerability to energy decline; and they are thus likely to react differently to the ensuing economic stresses. Full “democracies” according to the Democracy Index (Norway, Canada, New Zealand, etc.) are probably best situated to respond in ways that preserve democratic institutions and traditions. Nations currently listed by the Democracy Index as “flawed democracies” (United States, Philippines, Indonesia, etc.) are probably most at risk of shifting further toward authoritarianism via election. Countries that are currently “hybrid states” (Turkey, Venezuela, Pakistan, etc.) or “authoritarian” (Russia, Egypt, China, etc.) are more likely to experience revolutions or coups.

Countering the Risks to Democracy

How could nations in the “democracy” or “flawed democracy” categories resist a tendency to slide toward authoritarianism? It stands to reason that, if risk factors are present, reducing vulnerability would entail countering those factors as much as possible:

- Build and support independent media. Governments and leaders should resist the temptation to favor media outlets that simply parrot their own talking points, or that disparage current leaders’ enemies. Maintain full press freedoms, including legal protections for journalists.

- Work to limit climate change and other ecological drivers of human misery. This includes not only efforts to adapt to higher sea levels, but also to reform agricultural practices (carbon farming) and dramatically reduce carbon emissions in transportation and manufacturing.

- Work to reduce extreme political polarization. Avoid wedge issues. Nations with more than two major parties sometimes fare better at avoiding polarization.

- Support and strengthen democratic institutions. Prioritize fair elections (universal voting rights, public financing of campaigns, limits to campaign contributions, plenty of accessible polling stations that are open a sufficient number of hours, transparent methods of ballot counting).

- Promote tolerance. For a nation, ethnic, religious, and cultural homogeneity can be an asset in avoiding political unrest during hard times. But many nations are ethnically, religiously, and culturally diverse, and any effort to reduce that diversity would necessarily entail human rights violations. Nations with diverse populations must simply make the best of the situation, celebrating and honoring their diversity and protecting minorities.

- Discourage inequality. Most nations already counter economic inequality through progressive taxation and social welfare programs. But economic stresses from energy decline will require more creative thinking and experimentation, including encouraging worker-owned cooperatives and discouraging shareholder-owned corporations; implementing high inheritance taxes with no loopholes; and finding ways to reduce the role of debt in society.

- Minimize power of military and intelligence agencies. Keep the military separate from governance institutions. Keep the military budget within modest bounds. Don’t over-glamorize the military. And don’t permit “black ops” or domestic surveillance.

- Build low-energy infrastructure, habits, informal economy. This implies a change of direction for most nations, which tend to be hooked on large-scale infrastructure projects (highways, airports) that lock in energy dependency. Promote low-energy ways of providing for basic human needs, such as solar hot water heaters and cookers, walking, and bicycling.

- Promote population stabilization. Support family planning and elevate the social status of women.

- Build local food production capacity. Support small farmers, local food, and agriculture that minimizes dependence on fossil fuel inputs.

- Stabilize the financial system. Reduce reliance on debt in every way possible, shrinking the size of the financial system relative to the “real” economy of goods and services.

- Decentralize both the economy and the political system. Encourage distributed energy, local currencies, and local food. Allow city and regional governments to make all decisions except those that require national or international deliberation.

- Avoid being the target of foreign political meddling. Maintain vigilance with regard to electronic and propaganda warfare. Don’t take on big international loans.

These recommendations are far easier to spell out than to carry out. And at least two of them are seemingly at odds with each other: a nation that keeps its military and defense budgets at minimum levels might be morelikely to be the target of foreign meddling or intervention. Further, while most democracies are making at least some efforts along some of these lines, in many cases they are being overwhelmed by trends toward increasing polarization of politics and media, and increasing economic inequality.

Further, most of the above recommendations fall within the bounds of modern liberal norms and discourse. But, as we have seen, the entire project of industrial and social “progress,” as framed within the liberal economic tradition, has produced whole classes of casualties and rebels. The endemic risks to urban, capitalist, industrial societies stemming from the resentment and alienation described by Mishra—that lead increasingly to terrorism, religious fundamentalism, and authoritarianism—are inherently difficult to track or counter. To defuse this deep, amorphous threat to democratic values and institutions, perhaps something more is needed beyond the mere strengthening of media and democratic institutions—something that ties people back to the land and gives them both a “tribal” identity and a larger sense of purpose. A new religion might fit the need, but it is difficult to summon one at will. If advocates of democracy and cultural pluralism continue to fail to fill this void, authoritarians of various stripes will certainly seek to do so.

Are Dictatorships or Democracies Better at Responding to Energy-Economy Decline?

In the contemporary world, democracy is widely (though not universally) prized over authoritarian forms of government. This is certainly understandable: authoritarianism leads to the regimentation of thought and behavior, and often to the subjection of large segments of the population to psychological and/or physical violence. But are democracies inherently superior to authoritarian regimes in dealing with crises such as energy decline, climate change, resource depletion, overpopulation, and financial instability?

To adapt proactively to environmental limits and impending scarcity, governments may have to do some unpopular things. Restrictions on consumption (such as rationing) may be required, along with the encouraging of smaller families. Such policies cannot help but rankle, following decades of rising economic expectations. Economic redistribution could help reduce the stress of scarcity for a majority of the populace, but many will still resent the new conditions. Elected leaders may find it difficult to maintain sufficient popular support for such policies. Could authoritarian regimes fare better? A few historic examples come to mind.

During the early 1990s,

Cuba saw a sharp decline in energy supply due to a cutoff of low-cost oil imports from the now-defunct Soviet Union. At the time, Cuba’s food system was highly centralized and dependent on oil-fueled farm machinery and food transport. Cuban leaders responded to the crisis by decentralizing food production, reducing fuel inputs, and encouraging urban gardening. The result was a rapid and thorough restructuring of the nation’s food system that averted widespread famine. It is unclear whether such measures would have been feasible outside a command-and-control authoritarian political context.

Both China and Iran managed to substantially reduce their nations’ high birth rates—China (beginning in the 1970s) via its compulsory one-child policy, and Iran (starting in the 1980s) through vigorous but voluntary family planning efforts. Both nations formulated and managed these programs via top-down, centralized, and authoritarian methods.

North Korea has seen decades of relative economic stagnation, including at least one major famine. Yet the nation has remained intact through rigid centralization of its economy and its political and social spheres. All communications are censored, and all news is delivered through state-controlled outlets. The nation has racked up one of the worst human rights records in the world.

These examples might suggest that authoritarian regimes are inherently more resilient than democracies. However, there are instances where authoritarian regimes have instead proven brittle. For example, when the Soviet Union failed to deal with economic decline in the 1980s the government collapsed, as did the nation’s economy. In contrast, some democracies (such as the U.S. during the Great Depression and Britain in the 1930s and ’40s) have persisted during privation, though somewhat authoritarian temporary measures were instituted, including greater control of the media by government.

Many authoritarian regimes are poorly situated to help the populace weather economic crisis simply because their leaders are too obsessed with self-enrichment, self-aggrandizement, and self-protection. It could be argued that if a society is already impoverished due to the incompetence of its authoritarian leadership, its people will have fewer expectations to be dashed, and their standard of living will not have as far to fall before hitting subsistence level. But this is faint encouragement. There must be some better recommendation for today’s nations than “crash your economy and suppress your people’s aspirations now, so that they won’t be disappointed later.”

* * *

The relationship between energy, the economy, and politics is messy and complicated. There is not a simple 1:1 correlation between energy growth and economic growth: the Great Depression occurred in the United States despite the presence of abundant energy resources. Similarly, there will probably not be a strict correlation between energy decline and economic contraction.

One important wild card is the role of debt: it enables us to consume now while promising to pay later. Debt can therefore push consumption forward in time and (for a while, at least) make up for declining energy productivity. It would appear that the

“fracking” boom of the past decade, which probably delayed the world oil production peak by about a decade, depended on the power of debt. But when debt defaults cascade, an economy may decline much faster than would otherwise be the case (

default-led financial crashes have occurred repeatedly in modern history). And debt defaults can cripple the financial and thus the economic system of a nation, even one with plenty of energy resources (as happened in the U.S. in the 1930s).

As we have seen, dictatorships can sometimes adapt well to scarcity. We can only hope that, if scarcity does indeed lie in our immediate future, authoritarian leaders will minimize rather than add to their people’s suffering. Similarly, we should hope that everyone in democracies has access to information that helps them make collective choices that lead to successful adaptation to inevitable, impending scarcity. Unfortunately, flawed democracies may be particularly vulnerable when energy supplies decline. Given their political polarization and saturation with “fake news,” they are more likely to succumb to demagogues who promise to return the nation to a condition of abundance if granted extraordinary powers.

It is highly likely that, as events unfold, the causal criticality of energy decline will be hidden from the view of most observers, whose attention will be fixed instead on shocking but comparatively superficial and secondary political and social events. A more widespread understanding of the role of energy in society, and of the likely limits to future energy supplies, could be extremely beneficial in helping the general populace adapt to scarcity and avoid needless scapegoating and violence. Perhaps this essay can help in some small way to deepen that understanding.