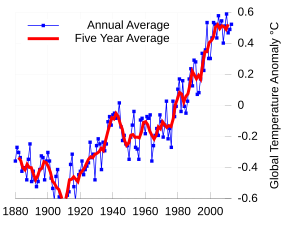

| 1880–2009 (Wikipedia) |

It is time to reframe the climate change debate.

Inadvertently, climate and environmental scientists have created an intellectual ecosystem that has created opportunities for contrarians like Lord Monckton, who have no scientific expertise, to thrive.

In the broader society this endless debate has resulted in a false binary: whether you “believe” or don’t “believe” in climate change, or more formally, “anthropogenic induced climate change”.

Too much effort by scientists has been wasted on attempts to persuade the public to think like scientists or embrace the scientific method. Large swathes of the general public will never think like scientists (you need only look at the persistence of astrology columns in newspapers to see this).

Nasty fights have been spawned, fuelled by the oxygen of the blogosphere. They have an almost theocratic edge about whose interpretations of a particular religion is doctrinally “correct”. Media coverage of the climate wars has become like celebrity gossip, but not as titillating.

This is a distraction from the work that needs to be done to tackle “here and now” issues like reducing the impact of bushfires, flood and cyclones, conserving biodiversity and restoring ecosystems.

Climate disasters have substantial social and economic costs. The need to reduce the impact of disasters is something on which we can, I hope, all agree.

These occur regardless of whether current extreme events, like bushfires, are within or outside the “natural range of historical variability”. Climate change is an additional effect, not the sole cause.

The current political response to disasters is to “rebuild”, with little evidence of any adaptation. For instance, genuine adaptation to bushfire demands retrofitting structures to make them more fire-proof, planned staged retreat from areas at high risk of severe bushfire and in some cases building appropriately designed bunkers to provide shelter from fire-storms.

More effective fuel management is required on the interface between urban and bushland areas. Equivalent engineering and planning responses are required to reduce the impact of floods, storms and coastal erosion.

More levies, such as those imposed following the Brisbane flood, are required to cover the full cost of government expenditure in disaster response and recovery.

Such levies, coupled with higher insurance fees, can send a powerful price signal of the cost of these disasters to the broader community.

As disasters rise in step with climate change this price signal is possibly more effective than the current “carbon tax” that has been designed to be invisible to most tax payers.

Such “bottom up” adaptive responses to climate change could have several enduring outcomes. Environmental policy debates can move on from arguing abstractions about plausible future scenarios to addressing specific issues that are consequential for citizen’s lives.

And adaptation will build a larger constituency of interest in the environmental issues. This will result in a greater interest in how resources are invested to tackle these problems.

The social, environmental and economic disruption of effectively adapting to climate variability will, I suspect, ultimately result in a hunger amongst the public and politicians for scientists' discoveries on the role of anthropogenic climate change in environmental variability.

Satisfying that hunger with knowledge about climate change effects will make possible futures much more real and make substantial social and economic changes more acceptable.

As the magnitude of the problems dawn on people I imagine more of us will voluntarily make investments to mitigate our own environmental footprint.

Ultimately, I think the ballooning costs of adaptation will lead to the inescapable conclusion for the great majority of people that top down control, through substantial taxation of greenhouse gas pollution, is cost effective and should be mandatory.

My argument is simply inverting the current debate from a fixation on “top down” regulation to avoid, or mitigate climate change, to greater emphasis on “bottom up” adaptation to climate change.

A sole reliance on centralised mitigation made perfect sense in the 1990s, when we had time to dodge the bullet of climate change. It is too late now and we need to adapt.

And, perversely the first adaptive step is to give up on the endless climate change debate and focus on surviving climate change.

David Bowman receives funding from ARC, NASA, TERN and NERP.

This article was originally published at The Conversation. Read the original article.

No comments:

Post a Comment