|

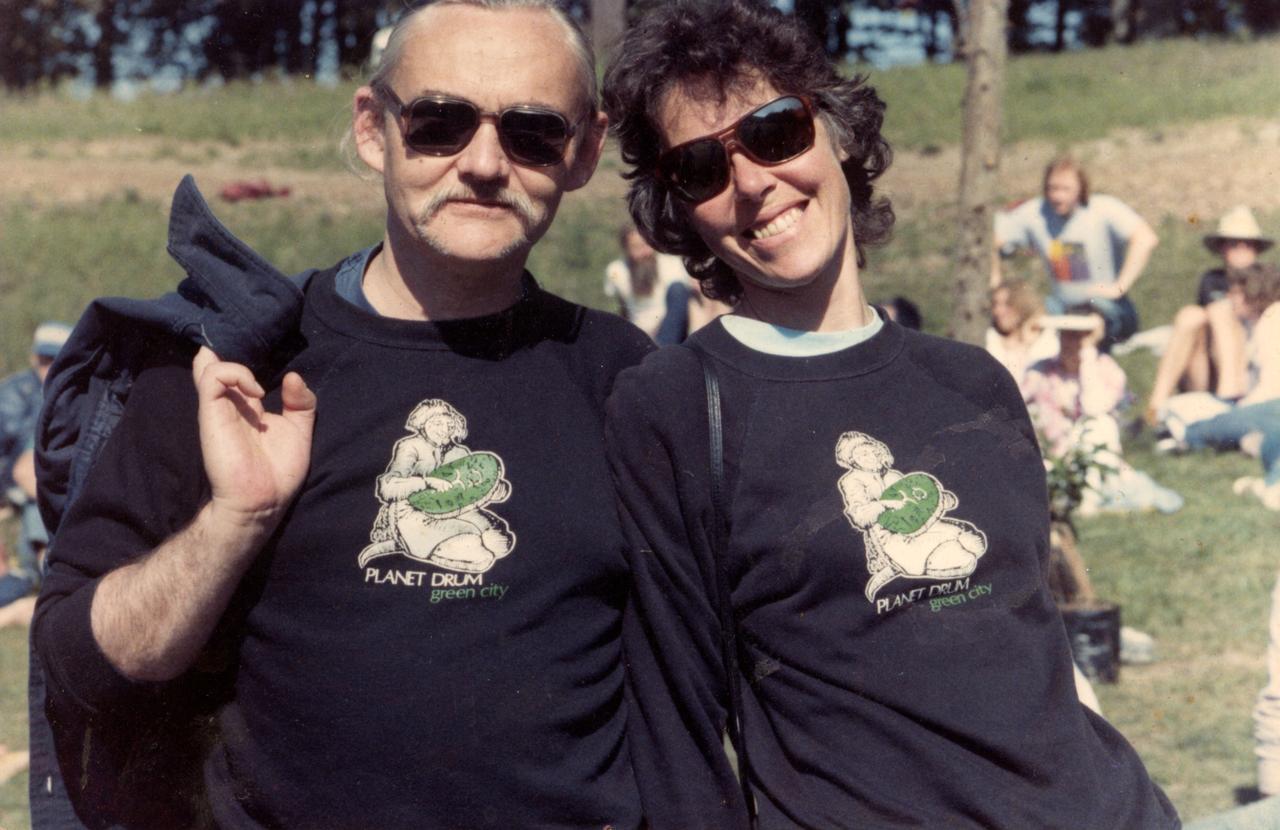

| Peter Berg and Judy Goldhaft at a bioregional gathering |

As he watched other ’60s activists become political insiders and dealmakers, Peter Berg held fast to one belief, even through his dying days: only radical change can save our planet.

“I don’t want to beat it,” Peter Berg says. “I want to seduce it.”

It’s March 2011, and the ’60s radical-turned-ecological visionary is dying. A tumor has paralyzed one of his vocal chords, leaving his voice scratchy and distorted, sounding, in his words, like a gravel truck unloading. "I want to seduce it into leaving,” Berg repeats. “Get it drunk and leave it in the gas station bathroom."

Berg sits at the dining room table of his green house in Noe Hill, a steep residential neighborhood in San Francisco, sipping chai tea. He still has long silver hair despite months of chemo and radiation treatments, and wears a brown long-sleeved shirt over several layers in the chilly spring air.

He can feel the tumor pressing on his nerves, low in his throat. "It starts usually in the left scapula, in that shoulder, the left side of my chest, then the other side comes on," he says. "It can be so strong that I can't walk." Despite the pain, he refuses opiates, citing a history of drug use that left him wary. "Doctors don't know what withdrawal is, really. They don't know what it's like. I do."

Peter Berg spent his life fighting - for civil rights, to end the war in Vietnam, and for cleaner, more holistic use of the earth's natural resources. Stage three lung cancer would be one battle too many, and he passed away shortly after this interview, on July 28, 2011, at the age of seventy-three, leaving behind his longtime partner Judy Goldhaft, their daughter Ocean and two grandchildren.

Intense, charming, abrasive, driven, Berg was known by friends and adversaries for never giving up and never compromising, no matter how big the opponent or how insurmountable the odds. His mission: To save humanity from its pathology of self-destruction.

"I'm an extreme personality. I tend to think in extremes," he says in March. "It's a planet-wide natural disaster we're living through."

Is he daunted by the enormity of the challenge? Berg leans forward in his chair, squinting hard at the absurdity of the question. "No, I'm turned on by it," he answers firmly. "It is the challenge. Oh no no, small groups of people cause enormous changes. I've done it."

* * *

Born

in Long Island in 1937, Berg grew up "up and down the East Coast."

After he dropped out of the University of Florida and served a

three-year stint in the Army, he hitched out to San Francisco in the

early 1960s and joined the Mime Troupe, a counterculture theater group

focused on civil rights and social justice.

He and Goldhaft lived together in their tastefully cluttered house beginning in the early 1970s. The interior is filled with potted plants, trinkets, bottles, candles and art from around the world, masks from Mexico, bowls from Asia. Out back is a messy yard with a small vegetable garden, flowers, apricot trees and a beehive.

He and Goldhaft lived together in their tastefully cluttered house beginning in the early 1970s. The interior is filled with potted plants, trinkets, bottles, candles and art from around the world, masks from Mexico, bowls from Asia. Out back is a messy yard with a small vegetable garden, flowers, apricot trees and a beehive.

Goldhaft carries herself with grace, her wispy gray hair pulled up in a bun. She cares for Berg in his illness, just as she's been by his side for decades, less of a public persona than Peter but a quiet partner in his life's work. She pops a cassette into the television in their the sun-filled living room.

Onscreen appears footage of the Diggers, their guerrilla street theater group that Berg co-founded in 1966 to oppose arbitrary authority, oppression of drug users and the Vietnam War. The film shows the Diggers taking over the San Francisco City Hall steps, playing music and messing with the suits.

A young Peter Berg with shoulder-length brown hair and a thin mustache confronts a Jehovah's Witness who was insulting the guitar player. "Who's a creep?" Berg asks him, staring with an intense squint.

The present-day Berg leans forward in his chair, an oxygen tube in his nose, watching his past with a grin. "I always told people that we were acting out the possibility of everything being free," he says.

The Diggers were behind the famous “Free Store” in Haight-Ashbury, and the group provided gratis food and shelter to the influx of pilgrims to San Francisco, striving for a society that functioned outside the confines of capitalism.

The film continues with scenes of the Diggers hanging off trolleys and tossing money to passersby, getting arrested and congregating at a "free theater convention" where Janis Joplin sings and the crowd dances, smokes pot, walks around naked, does whatever they feel like.

"I don't know whether you caught it so far, but this is anarchism," Berg says. "This is what anarchism is."

The scene crumbled when hard drugs and violence overtook idealism, and the Diggers carried a casket through the city streets to represent the "death of the hippy" in 1967. Berg left San Francisco and returned to the land, at the Black Bear Ranch in Northern California.

"A rather infamous place - free land, free sex sort of thing," he remembers. There, his thoughts turned to ecology - not a huge leap from street theater and activism, says former Digger David Simpson, seventy-four.

"One of the things that the Diggers really stood for is turf," Simpson says. "We could delude ourselves without a huge stretch that we were taking responsibility for our neighborhood and the place that we lived. That sense of responsibility for the place where you lived carried over."

Berg's time on the ranch sprouted the roots for the idea that he spent the rest of his life pursuing - bioregionalism. "Bioregionalism happened to correspond to the back to the land movement," Simpson says. "What we lived in, what we ate, wore and worked with was more a part of the natural land."

Berg took a road trip east across the United States, visiting various communes and creating an informal network of like-minded souls. In 1972, he traveled to Sweden to crash the first United Nations Environmental Conference, purporting to represent land-based communal groups.

Disappointed to be excluded from formal proceedings because he wasn’t representing a nation-state, he returned to California determined to pursue his own vision. Through collaboration with Berkeley professors Raymond Dasmann and James Parsons, the idea of a bioregion was born.

They defined it formally: “A distinct area with coherent and interconnected plant and animal communities, and natural systems, often defined by a watershed. A bioregion is a whole 'life-place' with unique requirements for human inhabitation so that it will not be disrupted and injured."

To

truly live bioregionally would mean eating only local food, produced in

a way that harmonizes with, rather than damages, local ecology:

building with local materials. A dramatic reduction or elimination of

fossil fuels. Reintegrating waste into the ecological cycle. Never

compromising sustainable living in the name of profit.

"Bioregionalism is as fundamental as you can get," Berg says. "Restore and maintain natural systems. Find sustainable ways to satisfy basic human needs. Food, water, culture, energy, materials for producing, building and to support the work of becoming native to the place.”

"Bioregionalism is as fundamental as you can get," Berg says. "Restore and maintain natural systems. Find sustainable ways to satisfy basic human needs. Food, water, culture, energy, materials for producing, building and to support the work of becoming native to the place.”

In the 1970s, mainstream environmentalism was mostly focused on lobbying Washington D.C. for policy change, so Berg went grassroots instead. He funneled his vision through the Planet Drum Foundation, the organization he founded with Goldhaft in 1973 to promote ecological justice in San Francisco and around the world.

He started sending bundles of literature to the network he had formed on his trip across the country and created a newsletter, "Raise the Stakes,” which resulted in a small but dedicated group of North American followers who hold bioregional congresses every few years.

"It just sort of spreads the whole ecological movement, getting people hooked up to the things they need to know," says Mary Meyer, fifty-six, a congress organizer from the Ohio River Valley watershed. "It's almost spiritual, too, learning to connect with place. Looking at where you live as not just a zip code but relating to the flora and fauna of where you are."

Would-be allies weren’t always on board and funding was always difficult. "People who support our point of view don't have any money," Berg says. "Some people don't want it, because it's too far out, it's too disruptive of a middle class lifestyle to live bioregionally."

He has been called a “thorn in the side of the environmental movement,” a label he was proud of. "Lots of people in the environmental movement say Peter Berg's a fool," Berg says earnestly. “The environmental movement needs a couple thorns."

The bioregional movement never gained much traction under its own name, but its principles have distilled into a sustainability ethos that has gained popularity since the turn of the century.

"A lot of twenty-somethings, young folks starting families, are very receptive to the idea of building sustainable communities, growing their own food, making those connections to place," says Ken Lassman, fifty-nine, a founder of Kansas Area Watershed Council, one of the oldest bioregional groups in the country. "That message is very fertile for what all is going on these days.”

Berg's

philosophies even found their way into electoral politics after a Green

Party committee met during the first Bioregional Congress in 1984,

planting the seeds for the political party. That's despite Berg's take

on politics: "If you're gonna do something alternative, you have to do

it outside society. You can't do it in the society. That whole thing of

reform from within is bullshit."

He also found willing ears around the Pacific Rim. The Australian government created a map outlining the nation's bioregions as official policy. In Nagano, Japan, in 1998, Planet Drum worked with local communities to mitigate the disastrous effects of Olympics-related construction on the environment. And his greatest opportunity came in a small coastal town in Ecuador.

* * *

Peter

Berg got one big chance to help build a sustainable city from the

ground up. In 2009, he marched through the streets of Bahía de Caráquez,

Ecuador, leading hundreds of residents walking with ecologically-themed

floats.

Spectators watched from the roadside while Berg started a chant of “Viva la Eco-Cuidad!” He led the procession to a stage, and lauded the town for its progress - but warned that much work remained.

Spectators watched from the roadside while Berg started a chant of “Viva la Eco-Cuidad!” He led the procession to a stage, and lauded the town for its progress - but warned that much work remained.

Berg and Planet Drum arrived in the small city of 20,000 residents in 1999. With gleaming white condos overlooking the Pacific Ocean, Bahía de Caráquez was once a thriving resort town for wealthy Ecuadorians, but was nearly obliterated in the late 1990s when a 7.1 earthquake toppled buildings and triggered massive mudslides on the steep hillsides, wiping out entire neighborhoods.

Newly homeless residents huddled in tent camps in the streets. "It was one of the worst-hit cities in all the West Coast of South America," says Patricio Tamarez, fifty-four, a native to Bahía. "We had seventy meters of mud in our highway."

Tamarez, an organic shrimp farmer, led a group to ask Berg to help rebuild Bahía as an eco-city. Planet Drum set up a volunteer hostel and transformed an unsalvageable barrio into a park.

To prevent future mudslides, ecologically-minded volunteers from around the world planted trees on hillsides in and around the city. Keeping with the principles of bioregionalism, only native species were used, like the thin but resilient Algarrobos, the massive and spiky Ceibos and the fruit-bearing Pechiches.

"Revegetation with native plants - that's a hell of a thing to do," Berg says, insisting the work not be called reforestation. “I really want to distinguish it from that crap. Reforestation serves the industrial logging interest. You're gonna plant nothing but pine trees because they're gonna grow fast and you can cut them down?”

Once

or twice a year, Berg visited Bahía to check up on the work and meet

the volunteers, greeting them with his particular abrasive style. One

traveler wrote online, "I came to the conclusion that he must be

mentally ill or a diabetic with extremely low blood sugar or something

like that," after Berg insulted her when she wouldn’t commit for a set

period of time.

Berg furrows his brow when reminded of the feedback. "I love it," he declares. "I hope it discourages anyone like her not to come. People don't understand the luxury of being able to volunteer. They come down thinking they're Jesus Christ."

In addition to revegetation, Planet Drum established a bioregional educational curriculum for local youth and a study abroad program for college students, and in 2007, Bahía was named one of the fifteen most ecological cities on the planet by Grist.

However, local officials still show little appetite for codifying ecological practices in policy, beyond what volunteers and concerned citizens are willing to contribute.

"It's gonna take some time before our country will look toward bioregionalism as a main source of planning and being able to sustain development and sustain life for future generations,” says Tamarez. “At least we're starting out now."

* * *

On

March 20, 2011, Berg, Goldhaft and some friends drive out to the beach

at sunset to welcome the vernal equinox, as they've done for decades.

It's been a rainy week in San Francisco, but as if to personally

accommodate the group, the sky clears above the ocean as the sun drops

toward the horizon. Choppy waves wash up foam from the Pacific, jiggling

in piles on the sand.

Berg is bundled in a black puffy coat and complementary black beret to combat the brisk evening air. Goldhaft wears turquoise, with matching plastic sunglasses. As the sun descends ever lower, Berg strikes a Japanese bowl and the chime rings out over the beach, clear and full, easily audible over the sound of the surf.

Slowly bobbing to the rhythm of the ocean, he chimes again as the others join in on tom-tom and harmonica. Berg grabs a conch shell and coaxes out its long, melancholy tone, then circulates apple brandy for warmth and morale.

Families, young couples and people walking dogs on the beach barely pay attention. The musicians are left alone as the sun sinks lower into the cloud band just above the ocean.

Berg's focus is on the big picture: where we go from here, what kind of world can be left to his daughter and grandchildren. "We have the same conditions imposed on us that all other species have," he says. "We die. We give birth. We have sex. We eat. We need resources.

"We're

actually the heirs of a tremendous legacy. Our species has been a

magnificent species. That to me is wealth. That's aristocracy. That's

nobility. Being a good human being is a good thing. That's the highest

you could do. And being a good human being right now requires that you

take a position of a consciousness perspective that's appropriate to

living in the biosphere as a good species."

The dangers are myriad, and urgent: climate change. War. Natural disasters. Food and water shortage. Nuclear meltdowns. “We have to control ourselves. Not for puritanical reasons but for reasons of survival," Berg says. "I want to do that." Save the world. Save humanity from itself. "That's what I want to do with my life."

In all his battles, he never declared a full victory. Racism, authoritarianism and imperial wars persist. Our ecological disaster is ongoing. The eco-city exists more in name than in practice. But Berg recognized the struggles were far bigger than he was. If he could provide an example, that was worthwhile.

"We've got to do it ourselves," he says. "People will do it. Then whatever society they come up with, that will be the society they get."

Soon, the sun has disappeared and Peter returns to the car to escape the cold. Goldhaft drives through the Haight where so much of their young energy was spent, but which is now filled with apparel and faux-hippie trinket shops. She notes the serendipity of the weather clearing up for the equinox, a simple pleasure for the small beach celebration.

"Most solstices and equinoxes aren't too cloudy," she remarks, pulling away from a stoplight. "We usually get a sunset."

* * *

Aaron Kase is a writer from Philadelphia. See more at www.aaronkase.com or follow him at @aaron_kase.

Photos courtesy Judy Goldhaft.

Photos courtesy Judy Goldhaft.

No comments:

Post a Comment